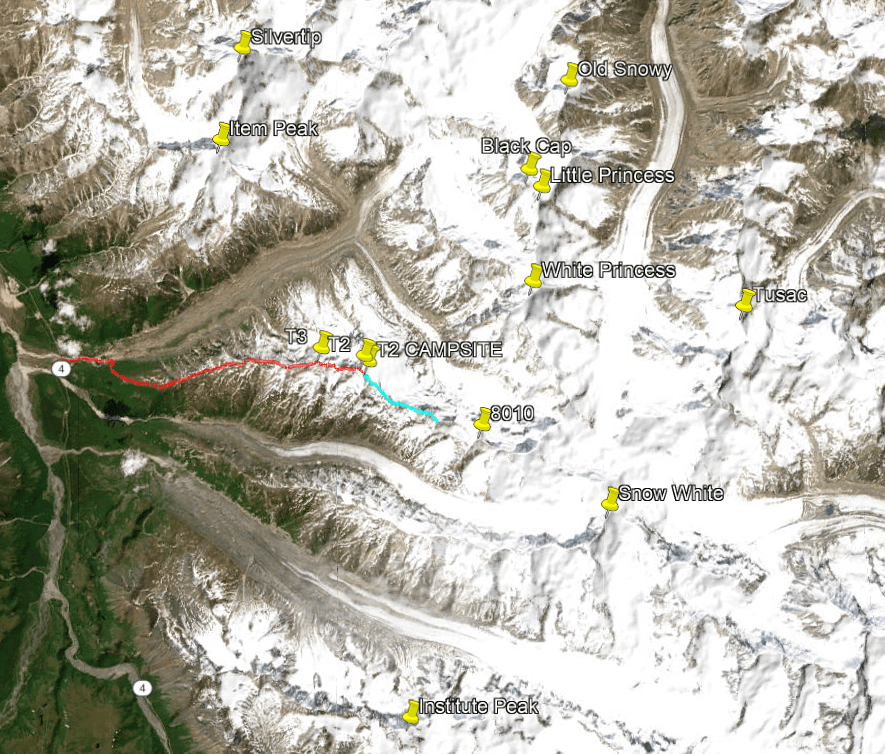

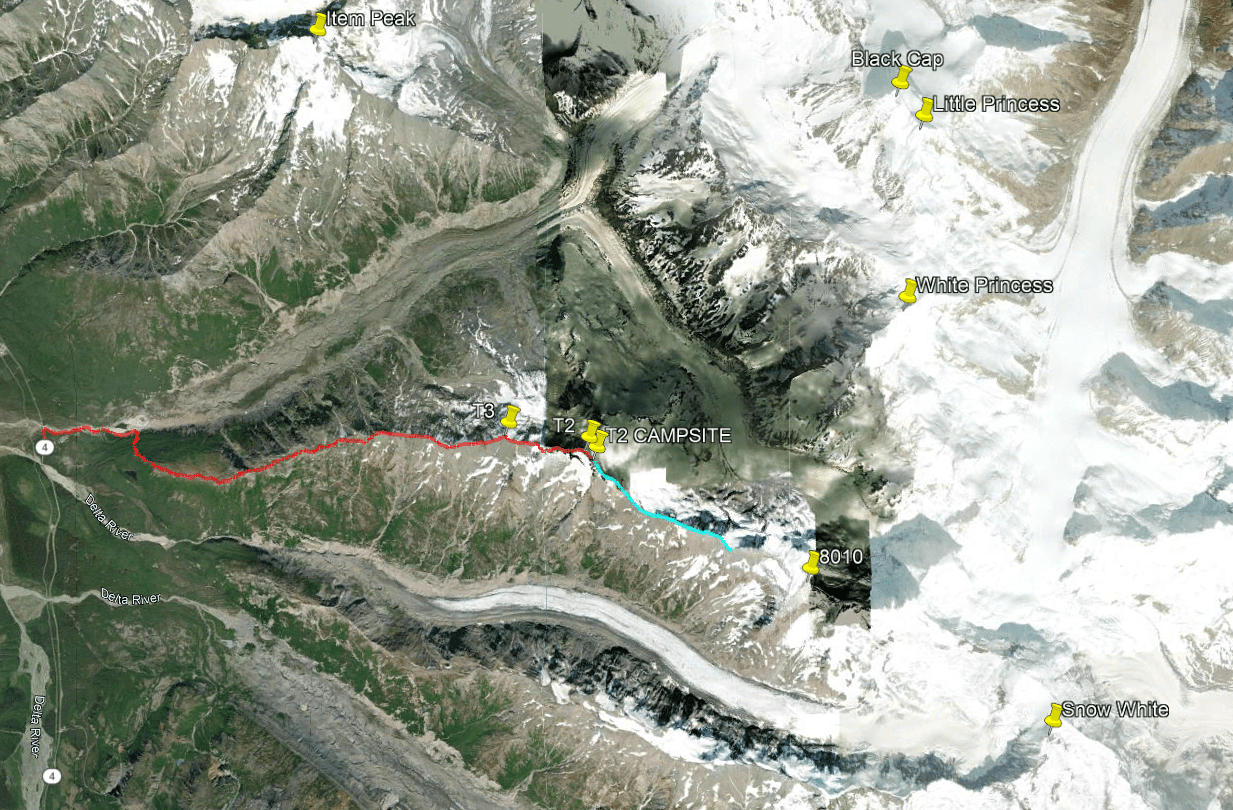

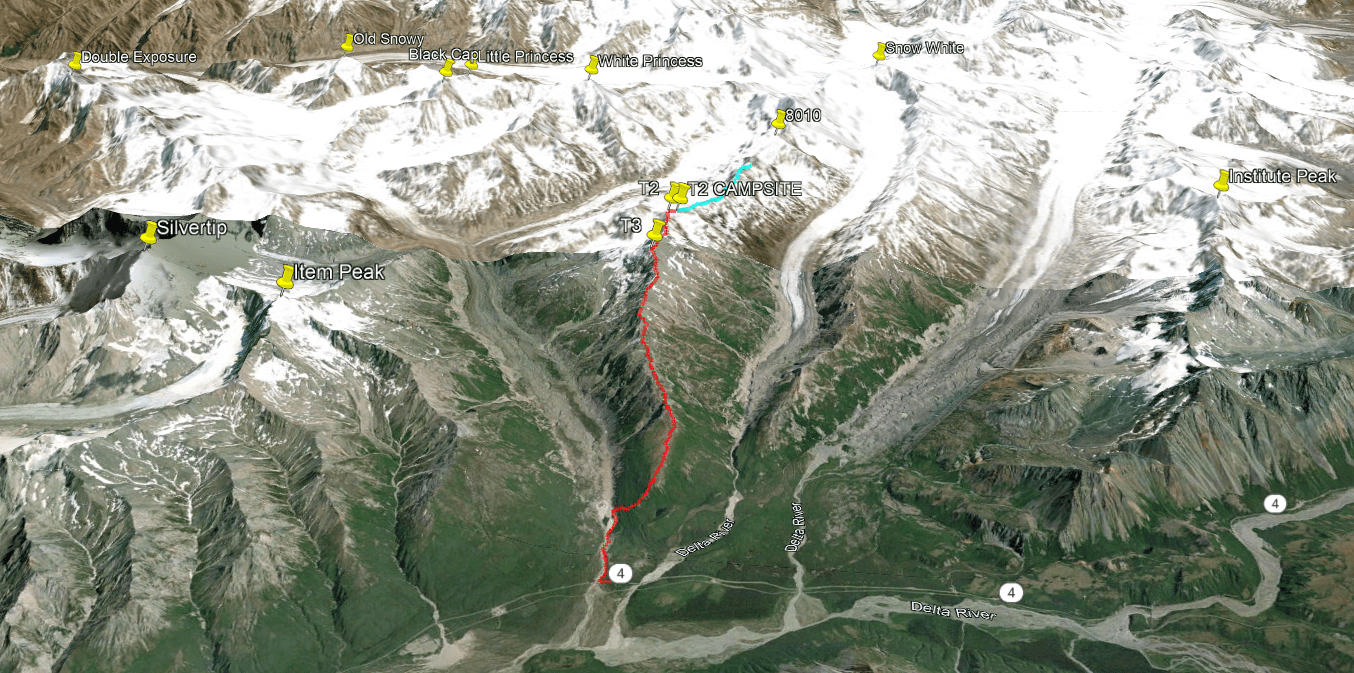

The “Castner-Fels Divide” is the southern ridge that borders the main body of the Castner Glacier and makes up the bulk of Triangle Peak. Near the highest point (T2), the ridge angles south and ascends as M’Ladies and Snow White, becoming glaciated at some point. There’s evidence Austin Post traveled up this ridge in the 70’s, and multiple routes up this ridge were drawn on a map attributed to him by the original Fairbanks mountain climbing community (info from Stan Justice and Dan Osborne). Though a lot of his names on the photo did not stick, it’s interesting to see old-traveled routes from when the glaciers filled the valleys. The Castner-Fels Divide is pictured below, the first major ridge on the lower left:

(A lot of these images, including these 1970’s photos from Wikipedia, are high resolution. Right click on the image, “Open In New Tab” to see the higher resolution photo.)

The alpine portion of the south Castner-Fels Divide is guarded by 300′ of willows and brush from the valley floor. Buck Wilson cleared a trail through the trees decades ago, which unfortunately has been lost to time. In 2019 the Alaska Alpine Club attempted to find Buck Wilson’s route but were unsuccessful. Nevertheless, they cleared a wide alder tunnel to the tundra of the ridge, ascending through the 3/4 mile of willows and alders into the alpine.

After seeing Stan Justice’s email in 2020 noting the route was clear, I drove to the Deltas and climbed a few miles up the Castner-Fels Divide. The ascent from the Castner Creek to the alpine took less than half an hour! Kiro and I camped about 3 miles from the road and weathered many rainstorms that rolled across the Deltas from the south. I hiked up to the first of many false summits on the ridge and marveled at the beautiful and endless expanse of terrain above me. I wanted to hike further but didn’t have the time or weather for such an attempt, but I knew the ridge would go, I knew fellow AAC member Chad Diesinger had summitted Triangle via the ridge in September of 2015. Stan said it’s allegedly been traveled all the way back to Snow White!

Aside from the temporary Caster ice caves, the Deltas are not well-documented. Most websites feature a few photos of White Princess, or an elevation and topo map of White Princess, and hardly any contain photos at all (even of White Princess). Very few other peaks get any attention; I’ve sought to change that with this website, as I hope others will enjoy this range as much as I have. Even if this blog gives you some idea of where you’re going in the Deltas, getting there still involves significant grit and a lot of travel over rugged, constantly changing terrain.

I’ve been visting the range since early 2011 and have noticed changes even in that short period of time. The first hill I skied down on the Castner has melted into riverbed, and the glacier ice Rick and I climbed that fall has since become a pile of rocks. I haven’t traveled up the Castner Glacier since 2019, but the route is always changing. The terminus briefly featured a spectacular ice arch-tunnel in 2014 and I heard rumor there was a lake in 2023, maybe there still is. For the most part, the most consistent feature is the southern portion of the moraine is the best access for the mountaineering: it flows from the relatively flat M’Ladies Branch and is that seems to have resulted in the smoothest moraine.

Fun fact: usually a mountaineer can double-pole miles and miles from “The Fin” (~ 63°26’7.28″N, 145°32’59.63″W) all the way to the road if the crust is good and if they choose a wise route.

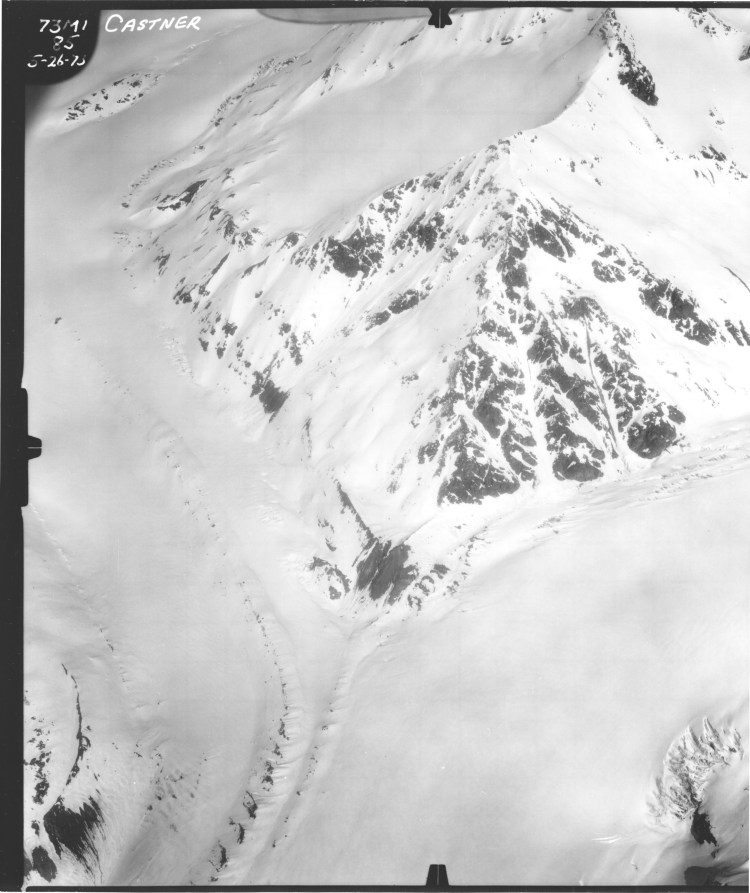

I feel somewhat duty-bound to share my documentation of the changing landscape. An aerial photo from 1973 (photo credit: Lary Mayo, USGS) shows just how much the glacier has diminished: hundreds of vertical feet of ice has melted in the last half-century.

The White Princess Branch of the Castner Glacier has melted substantially; the 2025 photo shows the same dark mass of rock above the plateau as shown in the 1973 photo. In the 50’s when the hut was just an idea, the plateau was 100′ above the glacier and visible from higher up on the central branch. In the 70’s, the glacier reached the base of the rocks on the right and I’m fairly certain the prominent red rock was barely uncovered. It now sits halfway up the slope. Regardless, the Thayer Hut is still accessible and the plateau is a wonderful respite from the lifeless landscape surrounding it.

Photo Credit: Lary Mayo, USGS (provided to me by Dan Osborn)

2024

In April 2024, Galen and I climbed Rainbow from the Richardson Highway. From the summit we noticed the high Delta peaks were curiously devoid of snow, likely due to high winds the previous week. The summit glaciers were unusually exposed: Silvertip, White Princess, and Old Snowy were all grey and blue expanses of ice. Terrifying to consider climbing, but spectacular to behold!

As we lounged on Rainbow’s summit col we had a beautiful view of White Princess, the crown jewel of the Deltas. White Princess tops out at 9,800′, far above the majority of the Range. Sought-after much more often than climbed, the approach to White Princess is a minimum 10 miles of slogging and the peak has roughly 4,000′ of prominence above the M’Ladies Branch of the Castner Glacier. I spent much of the 2010’s chasing after this peak before finally climbing it in 2019. Galen climbed it with Grant and Brian in 2013.

Every aspect of White Princess is draped by glaciers; from our vantage point on Rainbow we could see the southwest glacier flowing from the summit down to where it became an icefall, to the left of which the popular southwest ridge ascends the peak. Unfortunately we could not see the lower portion of the icefall, it was blocked by the Castner-Fels Divide.

From that moment, a plan started forming in the back of my mind. I texted Galen a month later, discussing ascending the Divide and hiking 9-10 miles back to the same vantage point we had on Rainbow so we could see the full icefall in all its glory after the seasonal snow had melted away. We just needed good luck with weather.

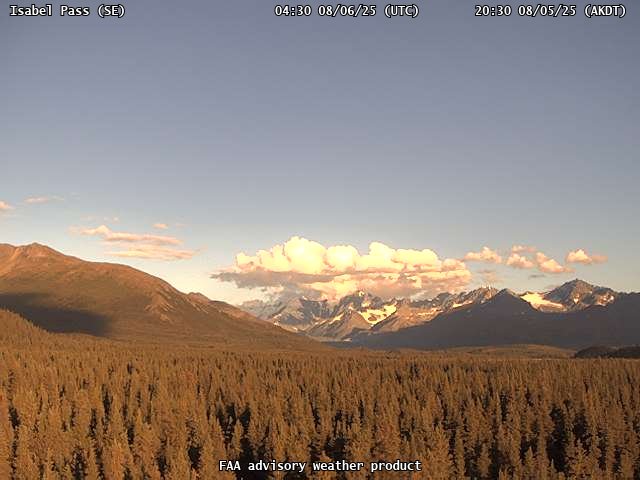

Luckily there is a webcam that looks directly at the Divide. I watched the weather for the rest of the summer, but never saw a good enough weather window to merit an attempt.

2025

Grant and I were scheming how to get out of town in late summer 2025. I had two adventures on Byron peak the week after Claire and I married, since then the weather had been phenomenal, yet not enough to draw me to the Deltas. A day and a half of relatively clear weather with a cloud ceiling above 10,000′ was my definition of “good weather”. Early August was my aim, as seasonal snow would be at a yearly minimum and new snow might not yet have fallen. I love this time of year on the mountains; not great for climbing, but summit glaciers are exposed and the bare ice formations are wild to behold. When ice is plastered to steep rock, weird and unique formations result.

White Princess’s summit glacier had been on my mind ever since I put my entire right leg into a crevasse on the way down it in 2019. I had ignored the advice to carefully place my feet in my old bootpack and instead plunged arrogant new steps, at least until I stepped into that crevasse. After seeing micro-crevasses on the ice of Double Exposure, I was very interested in how they formed on the steep flanks of White Princess. I realized this curiosity was an obsession all of my own, likely no one else cared about tiny summit crevasses. That’s their loss, as far as I’m concerned.

Grant and I thought we had a weather window the first few days of August and requested time off from work, but the weather window slammed shut the morning we were to depart. We were both bummed but had no desire to explore a 7,000′ ridge with a cloud ceiling of 3,000′. The spectacular views were kind of the whole point of the trip. However, as we were drinking mango mimosas on our friends’ deck a few days later, we saw the following week’s forecast had one solid day of high pressure in a two day gap between storms. With a better forecast, I talked Grant into taking two days off work again. I picked him up from his new house after work on August 5th and we drove 5.5 hours to the Castner River. A ptarmigan committed suicide an hour south of the Castner by flying into my driver’s side headlight, breaking the glass cover. The light still worked, so we finished driving at dusk and darkness fell around us as we made camp in the familiar woods.

We awoke around 5am on the 6th to a wet tent and clear skies. My MSR Hubba-Hubba is a great two-person tent and can withstand a good amount of wind, but that tight construction often retains too much moisture in the summer. Also, we were camped right by a raging river. We decamped and parked my truck at the large Castner Creek parking lot and hiked up the beach to the base of the ridge, noting the humidity hanging above the river rapids. In the distance we saw the shiny beacon of granite that marks the start of the alder tunnel. We followed my old gps track, and thought we were following the correct path up, but having never passed the shiny quartz we realized we were off trail. Fuck it, we’re bushwacking now.

We wandered up the slope through the woods, gaining elevation and traversing towards the gps track of the tunnel. After bushwacking 900′ up Byron peak many times, this was not much of an ordeal. The worst part was hunching under willows with a 60L backpack.

“This is easy schwacking, there’s not even spiky plants!” We mocked the brittle willows as we snapped through the foliage that obscured our path, but still it would have been nice to have a trail. Eventually, we found the trail and the rest of the ascent was a breeze. We de-layered when we reached the rocks above the treeline and left our unused saws and Grant’s bush gloves in the alpine by a bush. We had optimistically thought we might contribute to the trail, but our help was unnecessary. We hiked upwards, gaining the steep initial ascent to 4,800′ in good time, passing the spot I had camped 5 years ago and continuing upwards. At this point there was little wind and each of us had our own cloud of bugs. A few miles to the south two F-35s screamed past us, cruising east up the Canwell Glacier at speeds over 500mph and less than a mile off the ground. I reached the false summit first and saw two sheep that scurried further up the ridge. Grant joined me shortly after and we took a break, letting our clouds of bugs intermingle.

Occasionally you’ll notice a vast difference in quality of photos. The nice ones were taken with my fancy camera, all the others were iphone photos. The Iphone photos are mostly for reference, I took 3,000 photos with my nice camera.

Item and Silvertip were mostly in view, but Silvertip kept hiding its peak in the clouds. Item tops out just under 8,000′, Silvertip reaches around 9,600′ and is the most prominent peak on the west side of the range.

The previous day I had seen some research and found a large portion of the south side of the ridge was slowly sliding down towards the Fels Glacier. A landslide more than a mile wide! As we continued hiking up the ridge, we notices various…cracks and splits in the tundra indicating this was indeed occurring. Very very slowly, the slope was changing. The Denali fault is a mile or two to the south, below the Canwell Glacier. If there were a large (8.0-9.0 magnitude) earthquake right on the Denali Fault, the south face might collapse. I’m not sure how that would affect the top of the ridge, but it would be a dramatic change.

There’s a lot really interesting rock features on the ridge. I can’t really describe them, but the top of the ridge definitely feels like it’s slowly being pulled apart.

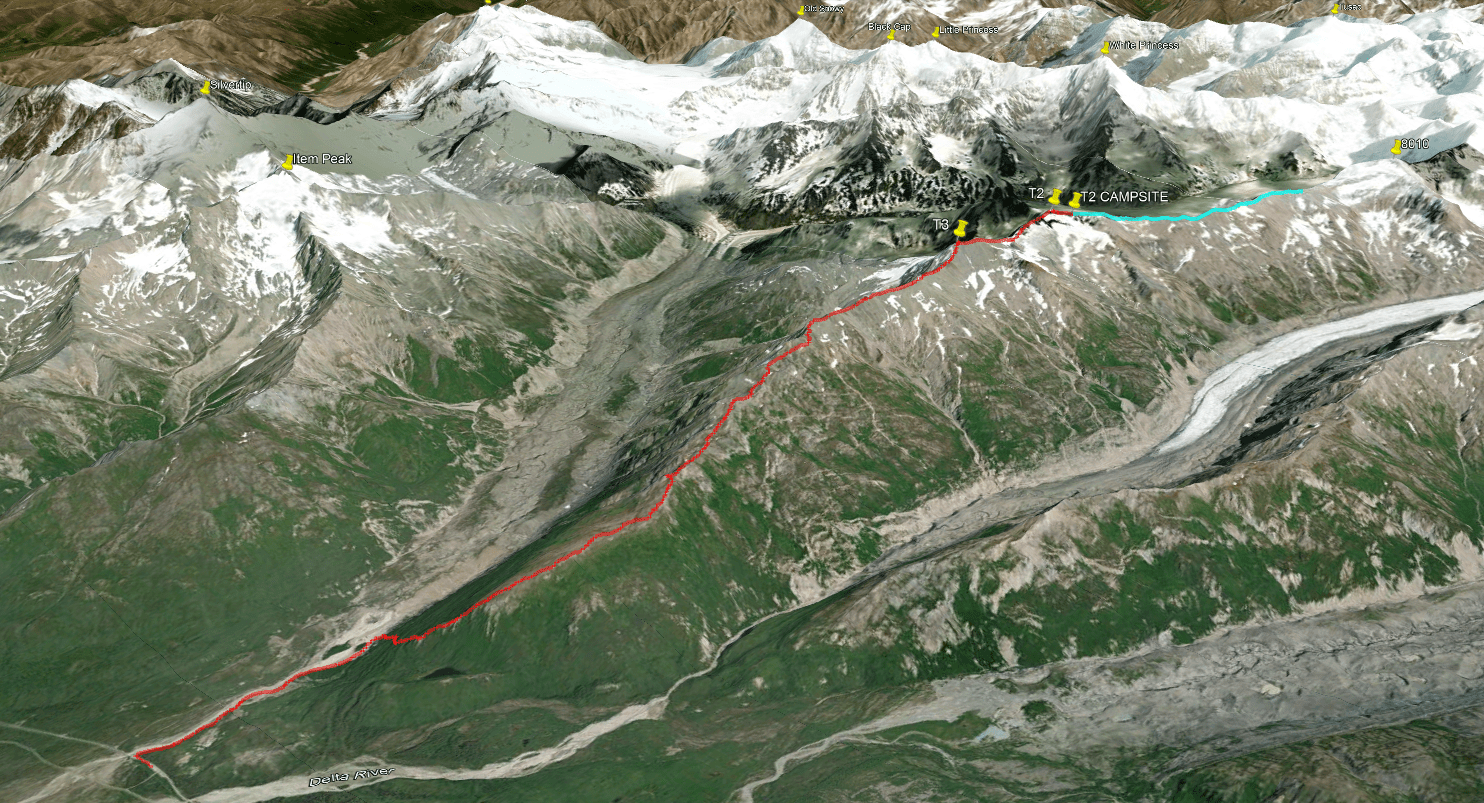

Further progress up the ridge added a light wind, for which we were grateful as it removed our bug clouds. We stopped at the first major deposition of snow and made water while we dried the tent and fly in the wind and sun. When we were scouting out this ridge, Grant and I were fairly confident we could make quick progress up the ridge until we ran into a glacier.

I emailed Stan about T2, the second major peak on the ridge, asking if it were glaciated. From imagery, it would appear the top might be iced or snowed over. This was a distinction with an important difference: whereas bare glacier ice was solid, snow could hide a bergshrund. Stan replied somewhat cryptically that he had gone past T2 and it appeared to be somewhat glaciated. “Somewhat glaciated” caused no shortage of consternation on our part. In preparation, we brought crampons just in case we encountered steep, hardpacked snow. We figured we’d be able to see the top of T2 soon. We were incorrect.

There was constant confusion between us over the names of the peaks. “We should be on top of T2 in an hour and a half. Dammit, I mean T3, the first peak.”

“The ridge is pretty chill along the M’Ladies Branch, but access depends on if we can get past T3…ugh I mean T2.”

On and on like this. It was as though Stan intentionally named these peaks in a confusing manner; why did he decide that the first major peak on the ridge should be named “T3”, not “T2”? Additionally, there is no T1 (unless that’s Triangle, which is not on the ridge), adding to the confusion. And how the hell can T2 be “somewhat glaciated”? What does that even mean? We figured we’d figure that out, and made note of any spot that might be a potential campsite along the way.

The ridge stretched for miles, and though we made continuous progress at times it felt like we were crawling. “Still better than hiking up the Castner Valley!” As we hiked further up the endless ridge, we kept hoping to get a glimpse of T3 or T2, and yet there was always more ridge in the way.

Finally, near T3, we reached a different aspect of the Castner-Fels Divide. There was a perpendicular ridge from Rum Doodle, to T3, to the Fels valley that had a small remnant glacier on its west side.

Once on the far side of this perpendicular ridge, the nature of the Divide changed. We began to hike alongside the massive cornices that feed the Broken Glacier to the west and could see T2’s lower remnant glacier/snowfield to the east. We also spied a lone caribou making its way up the snow. Separated from it’s herd, it won’t last the winter.

Grant didn’t bother getting to the tippy top of T3, but I enjoyed the vantage point with a grand view of the Castner Glacier and backside of Rum Doodle. But still, we had no view of T2 and its alleged glaciation. The consternation continued.

T3 Panoramas:

Grant bypassing T3:

The part of the ridge past T3 was far more spectacular than the previous section: massive cornices transitioned seamlessly into hanging ice at the top of the Broken Glacier. From below, the Broken Glacier seems nearly extinct, but from above the ice is still quite crevassed and thick, despite decades of climate change accelerated thinning. I occasionally would carefully step out to the edge of the ridge and looked over, making sure I was on solid rock and not overhanging scree. Only once I saw fresh rocks falling below me and wisely step back a few paces, but for the most part the ridge was quite secure. The thick hanging ice below me was gobsmackingly beautiful and I could see various layers of snow.

We had to lose some elevation after T3, dropping down to another remnant glacier at a col, just a smattering of ice filling a low point. There was some curious back rocks in one spot, we had no explanation form this formation. We hiked across the remnant glacier and back up the ridge towards the top of T2, which still had not come into view. I threw a few rocks onto the cornices next to us, hoping to cause a collapse, but they were far sturdier than snow had a right to be in late summer. As we climbed near the top of T2, we had the option of traversing below the peak or hiking the ridgeline to the top. We finally got a view of the summit from a few hundred feet away, it was not glaciated on our side so we decided to climb the ridge to the top. This section was not great climbing as all the glacial till was loose, but at least the scree was more solid than Chugach standards, likely due to the silt content.

The col between T3 and T2:

The 6 photos below are all taken from the photo above

The main body of Broken Glacier:

FINALLY! We spied the top of T2:

But we had a little more travel to get there:

BEHOLD: THE SUMMIT OF T2:

I topped out on T2 and found the far side of the peak distinctly snowy, immediately becoming a glacier. This…was different. Google and ESRI imagery showed this, but it was hard to imagine what a “somewhat glaciated” summit would entail. I encouraged Grant to top out with me and check out the landscape, after which we followed the ridgeline deeper into the mountains paralleling the M’Ladies Branch of the Castner Glacier. Grant’s feet were blistering, he didn’t have much appetite for more hiking and wanted to make camp.

Link to the youtube video, because WordPress sucks and won’t embed it

Although I wanted to camp further down the ridge, I offered a few options. After scouting a few hundred feet down the ridge, it was clear there was no camping spot in that range and we’d have to hike at least a quarter mile or so further to find flat ground. We could construct a tent platform on the ridge just past T2, or we could make camp on the snowy edge of the glacier on the northeast side of the ridge. Although the snow was tempting as it would make a quick platform, we decided to stack rocks and construct a tent platform on the ridge. The dramatic campsite sported a thick, increasingly steep glacier a few dozen feet to the northeast, and long scree slopes directly southwest.

We had a full view of the M’Ladies Glacier, as well as a partial view of the Fels Glacier. Triangle Peak’s summit ridge rose a half a mile away across the glacier from us. After getting camp set up, I told Grant I was planning to hike further down the ridge to attempt photos of White Princess. At this point, much to my frustration, the high peaks were still consumed by clouds, but the forecast was for clouds to clear sometime in the evening. I told Grant I’d be back by “7, actually make that 8pm”, and took off down the ridge. I had a few hours before sun would be off the SW glacier of White Princess.

I left camp around 5PM and made my way down the steeper, rocky part of the ridge until it flattened out into scree. Anxiety hinted I should probably run to maximize my range on this out-and-back, and running was easy with a much lighter backpack than earlier. All I had was water (which I never touched because that would waste valuable time), my camera, a jacket, and a tripod (which I also never used). I wanted to make it as far towards 8010 as I could and still be back by 8PM, I didn’t want Grant to worry about me while I was gone.

My attention was constantly on White Princess, I kept stopping when it looked as though the clouds might clear. The cloud ceiling raised and lowered by the second: 9,000′. 8,500′. 9,100′. 8,400′. 9,200’…they moved up and down the summit with the high winds. If I stopped and watched, I could see the pulsing of the dark clouds as they thrummed about the summit. As I had no guarantee the summit clouds would ever totally clear, I was repeatedly tempted into spending valuable time and camera battery taking 7+ photo panoramas of the cloudy summit, in hopes I could use photo-editing magic (dehaze) to clear them away. Would this entire trip be a failure in my mind if the clouds did not clear? I tried to steer my thoughts away from valutions of individual expereinces and focus on the whole, even though a clear view of the summit was the attractor to get out here. The trip so far has been a blast, it was great to be back in the big mountains with Grant for the first time in years and the views from this section of the ridge were even more grand than from T3 or T2 despite the clouds. I wish he could have joined me but his heels were forming large blisters and I didn’t blame him for staying at camp. The travel on this section of the ridge was easy and there were a lot of unique rock features and incredible glacier views in all directions. The clouds continued to undulate.

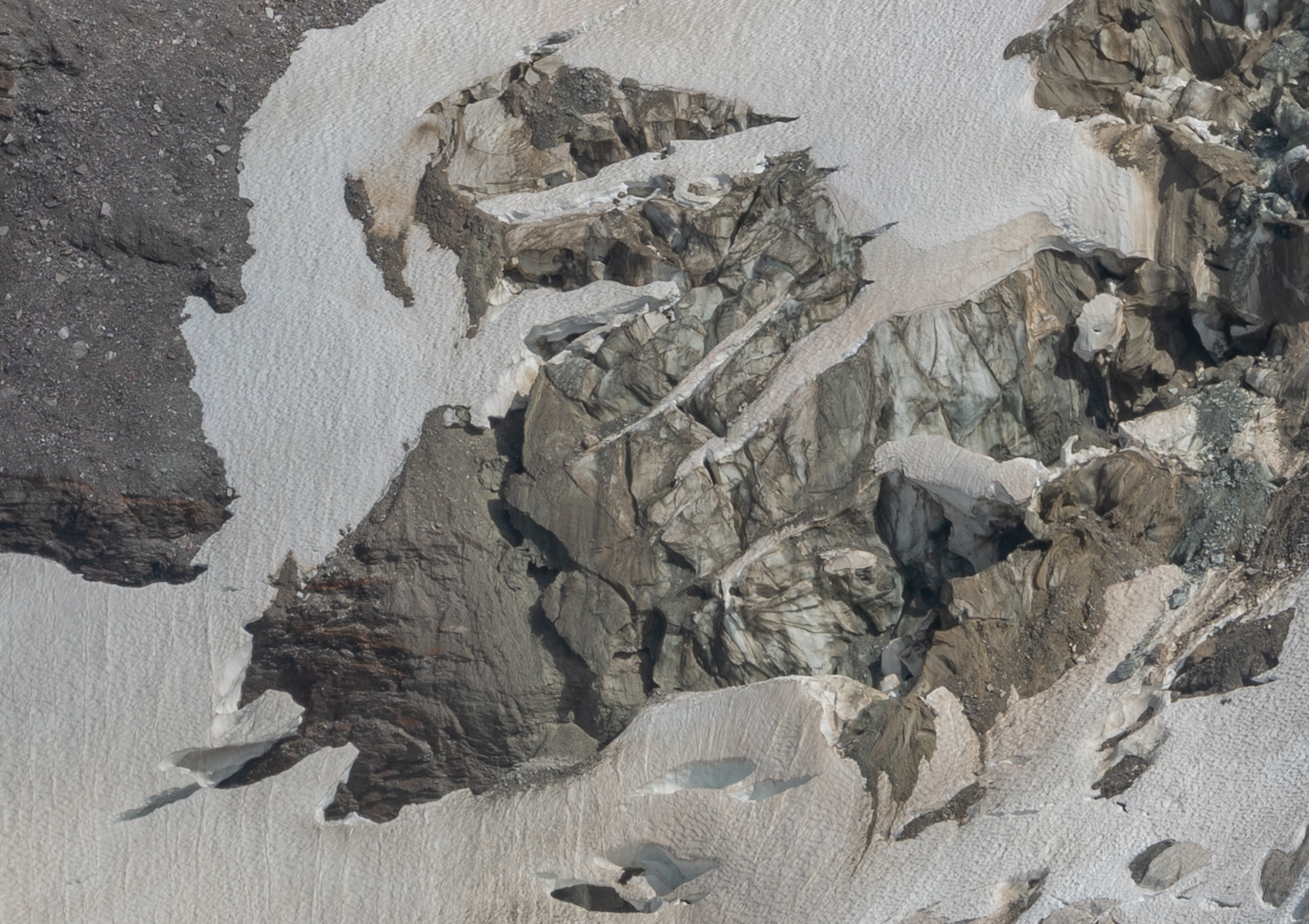

Finally, around 6:30PM the clouds on White Princess finally relented and gave me a view of the iconic summit fin. I actually whooped and did a little victory dance to the music in my ears. I was near my turnaround time and stopped to take more photos. The clouds were clearing off all the +9,000′ peaks, including White Princess, Silvertip, Blackcap, Little Princess, M’Ladies, and Double Exposure. FINALLY I got a view of the southwest icefall on White Princess, as well as the bare ice of the summit glacier feeding it. This was definitely the seasonal minimum of snow. Potentially an aberration; as it was a low-snow year for much of Alaska, this ice might not regularly be exposed even in late summer.

So about those mini summit crevasses…

That’s a nice view of the SW aspect of White Princess’s summit. But I want more detail.

More detail.

More detail!

MORE!

DETAIL!

Finally: 8,600′ to 9,800′ in crisp detail. There’s those summit cracks! Filled with snow but visible, I count at least 7 on the middle section of ridge and a few up top. It looks as though the summit fin is a glacial feature caused by the subglacial intersection of at least 4 ridgelines (NW, SW, NE, SE). There’s probably a little bump of rock on top of which the glaciers sit. It’s amazing the fin is glacier ice, I’d assume it would want to pull apart, the yearly accumulation of rime and snow must be sufficient to keep it from melting out. There was still a little seasonal snow on the slopes, but I’d never seen bare ice at this elevation in the Deltas before. Had I brought my 600mm lens I could have seen individual rime balls on the summit fin, but that seemed unnecessary when 200mm got me this level of detail from 3 miles away and 2,500′ below. There seems to be some sort of hole below the summit fin.

8010

I could see the end of the Castner-Fels Divide now, exactly where it became glaciated as it rose into 8010. The ridge smoothly transition into glacier and could easily be climbed to the ice. However, It would appear there is a crevasse/bergshrund that runs the entirety of the glacier that would require negotiation to summit or surpass 8010. At least, that’s what it looks like from my vantage point below, there’s potentially one snow bridge that could permit crossing. Once up on the glacier itself, the perspective might show there’s an easy path through the cracks. Traversing the scree below the glacier does not seem feasible, though if one were to sacrifice significant elevation the ridge ascending 8010 from the Fels would likely go.

I’ve included photos from 2016 I took from the Thayer Hut Plateau of 8010; there is definitely potential for the Castner-Fels Divide to melt out in the next few decades, opening access to M’Ladies Peak without glacier gear (though the top of M’Ladies will probably still require it).

Link to the youtube video, because WordPress sucks and won’t embed it

Not much more to say for the return leg of the trip; after taking more photos and staring longingly at 8010, I turned around and ran back, only stopping to take more photos. In retrospect, I wish I can continued about a half mile further: I think the view from the ridge on 8010 would be pretty neat, surrounded on both sides by the peak’s glacier. But I’m still happy with the vantage point I reached, and this thought gives me good motivation to make this trip more frequently than only twice a decade.

As I hiked up the final hill towards camp, Grant hiked down a few minutes to meet me just before 8 and we hiked back and hung outside the tent eating dinner and making water from the snow on top of the glacier beside which we camped. Triangle’s peak half a mile away was tempting in the evening light, we could see the relatively easy path down the slopes of the glacier and across a snowfield (with a glacier underneath).

I’d read a blog post that another hiker had successfully hiked to Triangle’s summit from this ridge, unaware his path crossed the head of the large glacier on Triangle’s east face. I was able to discern at least one crevasse his path intersected from the photo the hiker posted. Though we could see an obvious ramp down and path across to Triangle, both Grant and I had been to that peak before and didn’t feel inclined to risk glacier travel without rescue equipment this evening.

As we sipped on some whiskey and ate our rehydrated meals, we absorbed the views around us. This is truly the most scenic campsite in all the Deltas, from our perch at 7,100′ we could easily see almost every named peak in the Range, sans Item (hidden behind T2). The evening sun, while not alpenglow, still gave a glorious gold tint to our surroundings and I procrastinated getting in the tent until the light was nearly gone. It felt like the last sunset of summer in the Deltas.

Link to the youtube video, because WordPress sucks and won’t embed it

Thunder Pass. People used to cross over it.

The wind never abated, though it did have lulls. We made sure to anchor the tent firmly, I’m super happy with how well this tent deflects the wind. We watched two episodes of Rick and Morty on my phone and sipped from tiny whiskey shooters I’d brought (they were from my base camp cache on Denali, unopened) before falling asleep.

The next day we both woke up stiff and sore, though a few minutes of moving around helped. I resolved to replace my lost camp pillow, as the nylon stuff sack I used was an uncomfortable and slippery failure of a substitute.

When we emerged from the tent, autumn had arrived in the Deltas. The air was 20F degrees cooler, though it wasn’t quite as windy as the previous day. The high clouds filled the sky above us and ominous lenticular clouds were building on the high peaks of the Deltas. Grant and I acknowledged our narrow weather window was closing and it was time to go home. I took a few more photos, though I was mostly sated. In retrospect, I should have climbed back up T2 to get a better view of the area, but we were so sick of that mountain that my mind avoided thinking about it. I entirely forgot to take a panoramic photo from the top of T2, so I’ll have to go back someday and do that.

We made water, coffee, and breakfast, decamped, packed up, and started our return. Instead of the annoying but scenic traverse along T2’s ridgeline, we dropped elevation from camp immediately and traversed along the glacial till above the remnant glacier on the south side of T2. We took a very efficient path back down the ridge, the only detour I took was to top out on T3 again for more photos. Broken Glacier was still astoundingly thick up high, essentially a firn line that nearly became a terminal moraine, with only a little bare ice in between. Grant again didn’t bother with the top of T3.

We spied Old Snowy on our way back and the ice loss on that peak is noticeable, especially around the edges. The rocks that are melting out have been releasing scree, which will accelerate the melting of the underlying ice. I doubt there will be any glacial ice on the summit mound itself in a decade, though the famous Ramp will likely still hold ice for a bit longer.

Old Snowy in 2025:

Old Snowy in 2010:

Old Snowy, 13 years later:

Old Snowy 2024:

A year and a half later in 2025:

I feel lucky to have walked on the summit while it still holds ice.

White Princess is faring better, but the summit glacier is also thinning on the edges, as well as the terminus. A snippet of the larger Deltas photo from the 70’s, shown below, shows the extent of the glaciers before humans accelerated climate change to its current (still increasing) rate. The glacier coming down the northwest shoulder of the summit no longer has a valley feature, that is all moraine. The glacier on the west side, between the west ridge and the southwest ridge, used to fan out but now has receded to just a remnant in the seat of the bowl.

I try to make these observations without too much attachment. I am lucky to have been born in time enough to find glaciers useful for climbing in the Deltas, ascending their flat expanses and slopes instead of the underlying unstable till. One day a generation of climbers will be born who only climb moraines, occasionally spying glacier ice through a crack or melting face. The next generation will never know glacier ice, except in the high mountains.

Trying to leave these thoughts behind me, I would hike ahead of Grant and his blistered feet, take photos until he caught up, then hike ahead once. I put my camera away a few times, thinking rain was imminent, but it never touched us. We had nice views of the Fels Valley with Snow White at its head to the southwest, the Canwell Valley on the other side of the Fels-Canwell Divide, as well as Silvertip and Item to the north.

When we reached the brush and rocks above the alder tunnel where we had left our bushwacking stuff, we found a creature had disturbed them. Not only were holes chewed in Grant’s gloves, my saw had been chewed up and thrown off a small cliff! We packed our belongings, hiked down the alder tunnel, made a slight cairn to mark the slope, and got back to my truck before the rain hit. I taped a plastic bag over my headlight’s hole from the ptarmigan impact and we drove back to Anchorage, finally ready for autumn in town. The Deltas were socked-in for the next few days and when the clouds cleared there was fresh snow down to 4,000′.

Update: I drove through the Deltas in late August with my 600mm lens and snapped some photos.

2 thoughts on “The Castner-Fels Divide (T3, T2)”