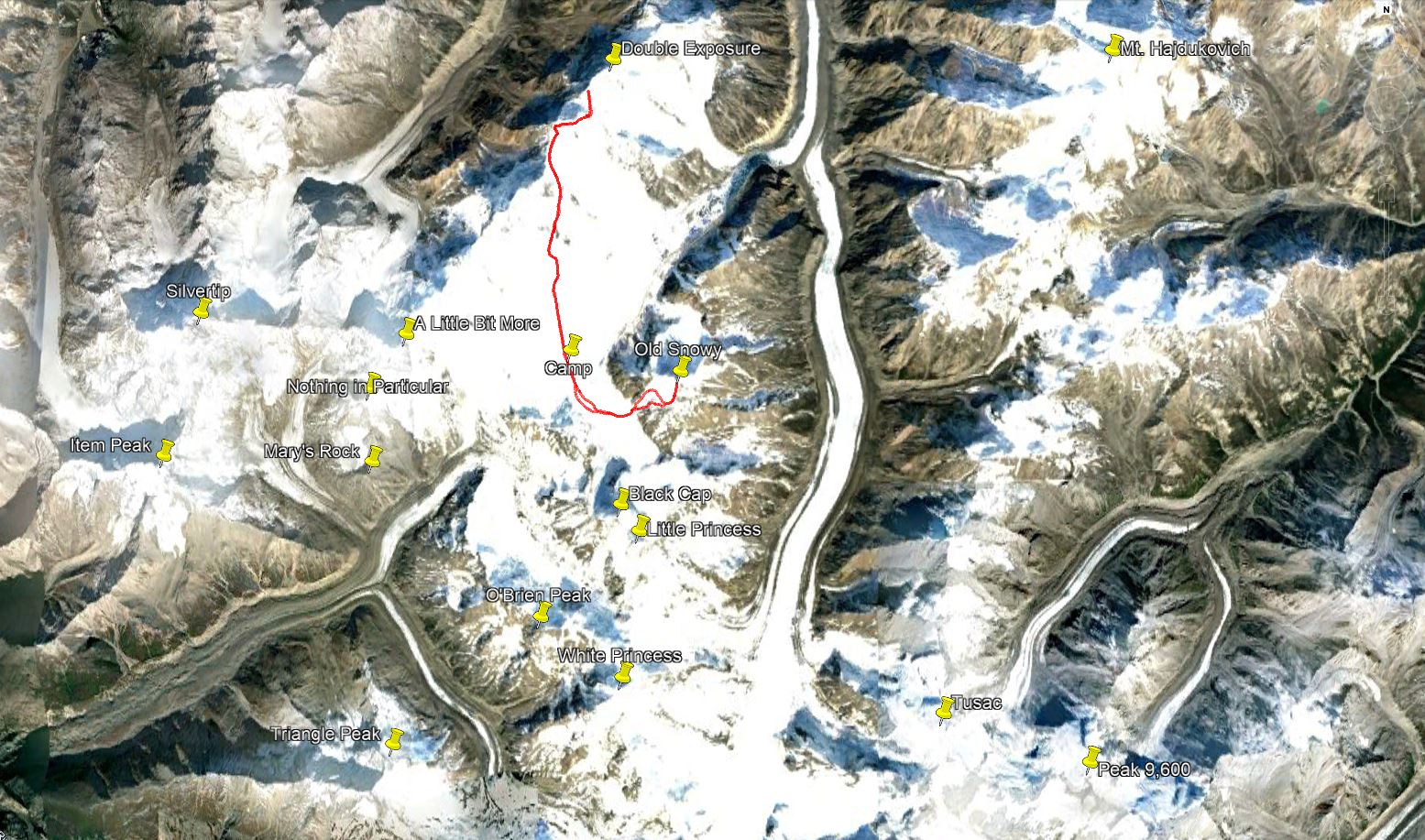

Old Snowy Basin, as seen from Blackcap

Old Snowy Basin, as seen from Castner north rim

The weather report from Rick on Saturday afternoon announced the end of the clear weather we had been experiencing; since Thursday’s eerie calm, both Friday and Saturday had been quite windy. Sunday was set to be stormy by noon. I informed Quinn, who had been in the tent all day for a second day recovering from his illness. He rallied that evening, and at 9:40PM we were skiing west towards Double Exposure. I had a weird feeling in my gut (literally) but decided to ignore it. This weird feeling began to influence my mood towards sour as we skied away from camp.

We could have tried Blackcap or Little Princess, but Double Exposure was a peak I’ve wanted to climb since I first heard about it over a decade ago in the Deltas guidebook (written by Stan Justice and available at Beaver Sports) and Quinn was equally interested. Route details are lacking, except for noting the 2500’ drop on the east side of the ridge was comforting compared with the 4000’ drop on the west side of the ridge. Jalen and some others had made the 2nd ascent, the 3rd overall, of the first ascentist’s route (2nd ascent of the peak was via a gully on the west face, apparently a dog was on the team).

With a route plan in mind, we traveled over two cols to gain and maintain elevation as we skied the roughly 3.5 miles to the ridge. Starting the ski at night was weird for me, there is comfort in daylight that cannot be fully-appreciated until one embarks on a sunset journey into deepening darkness. “Darkness” is relative, as it is summer in Alaska, but the looming clouds cast an ominous shadow over the icefield even with “endless daylight”.

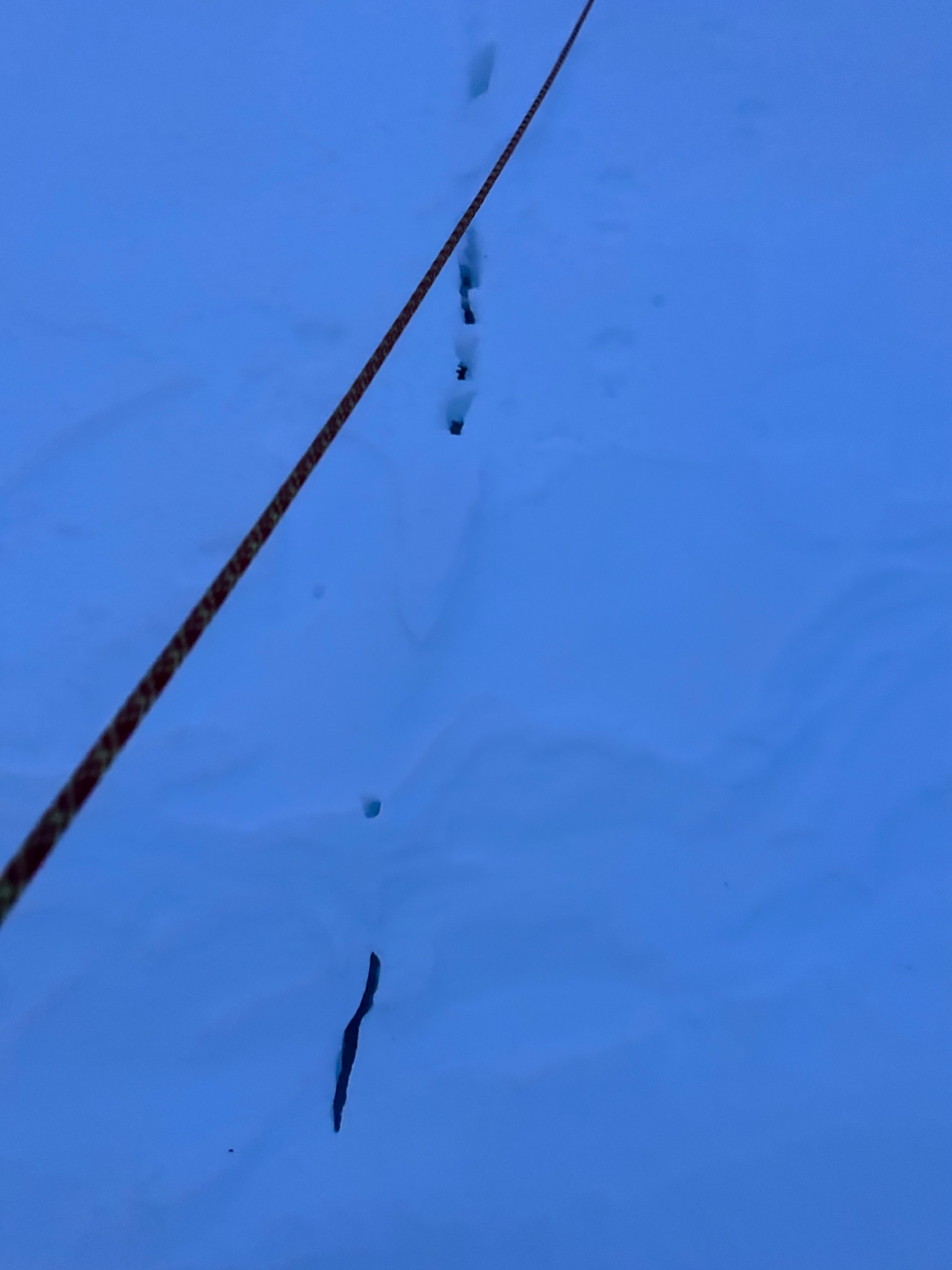

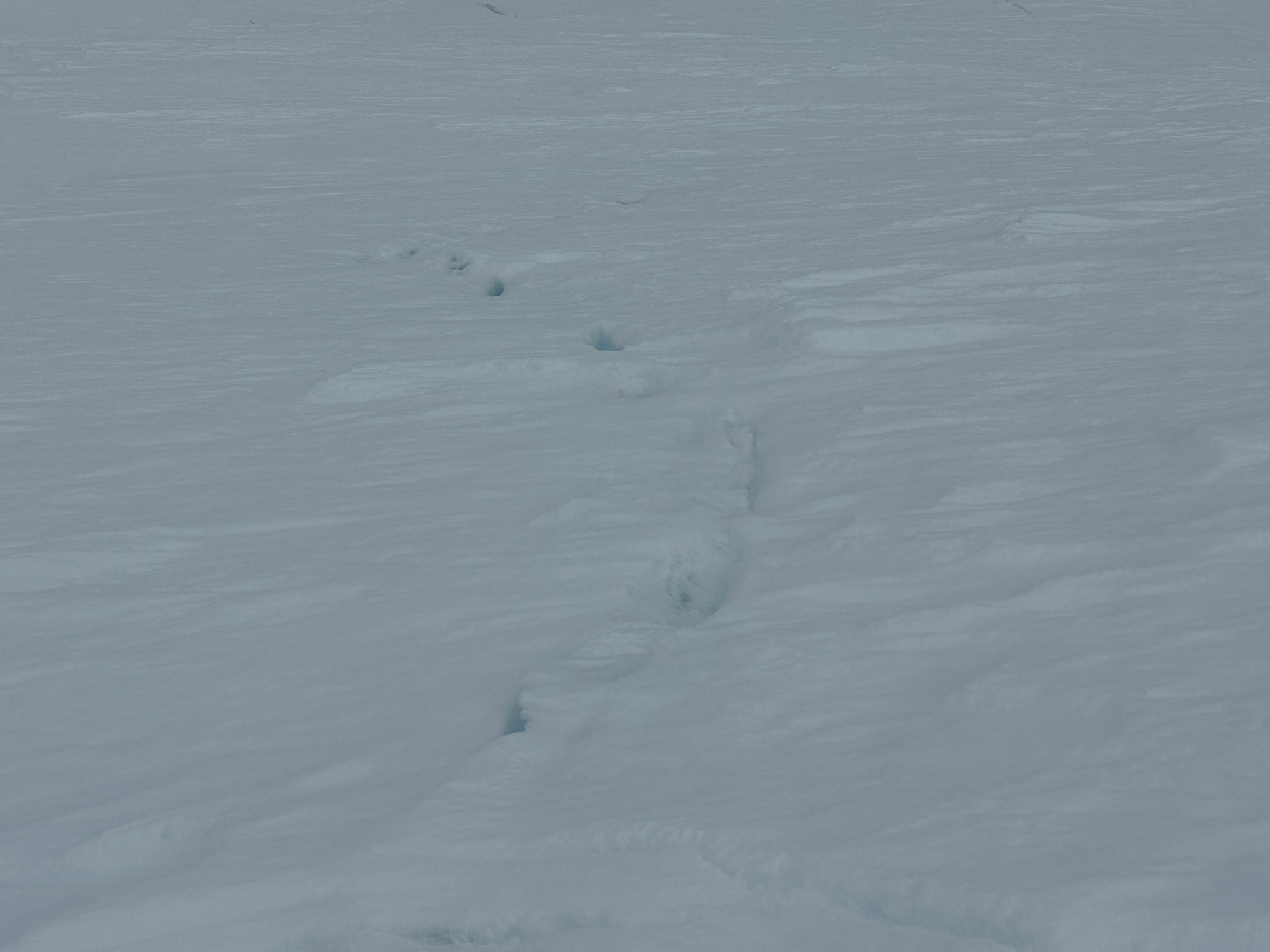

We traveled across the glacierscape I had been observing for the past few days while building camp. Climbing Old Snowy on Day 1 gave us key information about snow conditions and the topography of the Old Snowy Basin, mainly the locations of snow bridges. As we traveled up one of the glacial hills we got an up-close view of the sea of crevasses we could see from camp, waves frozen in ice due to the glacier traveling over varying underlying terrain. I angled our trajectory to traverse the crest of the glacial hill so we could easily spot the main snow bridge to cross. I used a number of my wands to note our path across this section; I found myself wishing I had about 30 more. We watched the sun set on Old Snowy and Blackcap and continued skiing into the night.

Despite the sun setting, we made good time in the shade and arrived at the ramp to the first col at 10:45PM and climbed to the first col without incident, initially on skis but switching to crampons when the snow steepened and hardened. We emerged on top with next to zero visibility in terms of the route down, as well as a large, mostly-covered crevasse/bergshrund right next to us. Great.

Thinking fast, I planted a wand right below the pass, then backtracked and grabbed many rocks as I could carry and began to toss them off the top of the pass down towards where I assumed there would be a valley. Sure enough, the rocks landed on a surface that suddenly seemed much less-steep than in the dim flat light. I skied to my rocks, picked up most of them, and restarted the rock-throwing process. We were able to continue in this manner all the way across the glacier until we found the next snow incline to climb. I left my rocks behind in case we needed them on the way back.

By the time we reached the top of the next col we were on crampons once again, the hard snow on the ramp below the col required spikes, not skins. Finally in view of our objective, I cursed this mountain for existing as a draw of curiosity for such a large portion of my life. I was vaguely aware that my mood was being influenced by the extreme indigestion I was currently experiencing, but the feelings were real in the moment regardless of their genesis. My friend Jalen Cox and a few others made the second known ascent of this route the previous year’s spring and had given us some good info on the route. I watched their whole ascent from the comfort of my couch while waiting for my hip to heal from surgery and eating ice cream, refreshing their inreach location every hour.

Not one to skimp on research, since that time I’d gleaned and scraped any useful information about this mountain from the American Alpine Journal, to another blog (https://fromrockstorivers.com/2021/04/23/old-snowy-and-the-8750s/), to instagram posts carefully screenshotted and archived; I’m a hoarder when it comes to beta. From what I recall of Jalen’s home slideshow, there was a tricky rock section at elevation, but otherwise the ridge was pretty chill.

Due to an instagram post, as well as ESRI imagery, at the top of the second pass I knew there would be a sizable bergshrund to potentially negotiate. Sometimes they span the entire heads of valleys, though often most of the crack is buried. My old dog Kiro nearly fell into the bergshrund at the head of the Byron valley glacier, back in 2014 before the valley portion of the glacier melted away. I barely caught him by the hind leg just as he was falling towards the maw and I’ve been wary of bershrungs and wet rock ever since.

In 2018 I made a desperate jump off a snow bridge covering the bergshrund at the head of Portage Glacier as it collapsed beneath me. These things terrify me now.

Putting our crampons away, Quinn and I reapplied our shred sticks and started traversing below the 8000’ pass that serves as the start of the route proper. The bergshrund to our left was spooky to observe as we quickly skied over the snow bridging it at 12:40AM.

Very soon after, the snow turned hard again so we again switched from skis to crampons, a process that took a little more time for Quinn because his crampons weren’t newfangled-foldable lightweight crampons like my own (petzl leopard). We could barely see the false summit of Double Exposure from the top of the pass, still so very far away. I stared up at the mountain and cursed it as my gut rumbled; my eyes were no longer susceptible to foreshortening in the Deltas and I understood just how much more effort would be required to ascend this mountain. Additionally, I always keep in mind the journey just to get to this point would need to be retraced entirely on our way back.

I lead out across the pass, for a while on top of solid windsuncrust. Eventually I reached a section where the 3”-4” of crust would not support my weight. Each step barely held until fully weighted, then shattered, plunging my legs into deep faceted snow up to my knees and hips. My hips were doing fairly well since surgery over a year ago (the recovery is long), but the amount of force my hips were absorbing started to worry me. This experience took on another dimension in my mind with the bergshrund haunting my memory. Every step caused anxiety spikes, wondering if this step was the one to sink me into inky blackness. How about that one? And the next?

Eventually my mind started to revolt, as this was the absolute worst type of snow climbing I had ever experienced. It took so much effort to make so little progress and concern for my still-recovering hip’s durability came to mind. I gave up the lead to Quinn, who immediately climbed higher up to continue the traverse, thinking perhaps my fears were correct and I had actually found the buried bergshrund over and over again. They can be completely filled with snow, as we saw at the base of Old Snowy. Quinn had either good fortune or impressive skill finding supportable snow and I was relieved not to be leading this section anymore. The traverse from the second col to the base of Double Exposure was nearly 3/4 of a mile.

I told Quinn I was taking Double Exposure off my List (Snow White, M’Ladies, Old Snowy, Double Exposure); I had that right. I no longer wanted to go up this mountain that would require so much effort from me and that realization was of keen interest to my slowly-atrophying climber’s brain. What was I doing here? Is this the inevitable result of curiosity crossed with competency? Why was my gut hurting so much?

Just before 2AM, Quinn reached the base of the ridge that would serve as access to the mountain-proper. Jalen’s party had ascended via a memorable and distinctive snow gully that broken through the rockband guarding the edge of the ridge. Quinn and I had previously analyzed my photos taken on our flight in, we could tell this would not be an option as it was currently totally filled by an overhanging-cornice. Instead, we continued passed the rockband in favor of steep snow slopes. Quinn took a few initial steps up and found the same breakable crust I had encountered earlier. Rather than giving up, Quinn heroically made upwards progress as I watched in disbelief. Surely he would turn around. No way he keeps going. I was ready to bail and already told him so on the traverse. Nevertheless he continued upwards until the snow thickened enough to be barely supportable.

The snow slope we climbed was underlaid by rocks that had been absorbing heat and transforming the snow into facets from the bottom up, even as the sun metamorphosed the snow into crust from the top down. The result was the breakable, horrible faceted crust wherever there was scree. Quinn placed two pickets on his ascent, as well as left me a nice bootpack to climb, which I greedily followed. I had the realization any alpinist not in the lead is practicing vulture alpinism. Quinn belayed me up to the second solid picket, then found his way through the shale pile at the top of the snow. Once he was above it I followed, not bothering to remove my lightweight crampons. This was a mistake.

This portion of the ridge topped out and became glacierscape, as fantastic as it was confusing to comprehend. It seemed as though ages, wind caused snow to accumulate in teardrop-shaped piles on the west side of this ridge, forming into glaciers. But the piles are pulled in multiple directions, causing small cracks to form that start as horizontal cracks down and across the ridge that slowly bend downward. Similar to Institute Peak’s swoops, there were sections that continued to steepen until they plateaued. However, unlike Institute these were formed of glacier ice and various cracks ranged across the snow-covered ice. Most of the visible cracks were pencil-thin to foot-width. My crampon fell off as I was descending, the first high point on the ridge, though not due to a crack. Inspecting my new-fangled lightweight crampon, I discovered the cord that connects the toepiece to the heel piece had been mostly-severed by the shale….great. Now another anxious thought to bounce around my mind. Good footing is important on a climb called Double Exposure. I fitted the crampon back on, hoping it would stay on. It fell off again about 20 minutes later.

As I followed Quinn up the ridge, I noticed how truly chill the travel was. No wonder route information was scant, there’s not much to climbing once on the ridge. Having passed the rock section, I was feeling light and excited at how quickly we were advancing up despite my lacking the desire to climb higher. The curiosity battled the pain in my gut. Only 8 other people (and one dog) have been on this ridge, as far as I knew. I opened my mind to the possibility we could actually reach the ulu blade of the summit, something I had refused to consider in order to avoid forming expectations and potentially experiencing disappointment. As we neared the first steep snow obstacle, a false summit bump on the ridgeline, I was walking around sideways to consider how to climb it when my crampon fell off. This crampon problem was getting about as annoying as the gas in my belly.

The false summit ended up being less-steep than predicted and we simply climbed over it and continued onto a knife-edge, Quinn placing a picket for protection. I also left a wand somewhere on the ridge for good measure. This peaky feature was much more intimidating from the sky and glacier than the ridge.

We traversed the mellow knife edge which lead to a small summit we didn’t climb; with the way snow had filled in the crevasses there was no need to climb that particular low summit; instead we traversed the glacier that clung desperately to it’s west face, a bowl with large crevasses crossing lengthwise. I’m unsure if all 6 known others who previously climbed this ridge traversed the bowl, but walking on the ice between crevasses just made sense to us with all the extra snow. Plus, we later found out the ridge after the false summit was broken by a crevasse. Into the bowl we went, one of the most beautiful and mildly terrifying traverses I’ve walked. The fear was all mental due to knowing the risks and hazards (4000′ drop); the walking was easy.

The 4000’ drop to the west was less astounding due to the distracting number of large crevasses directly below us; it wasn’t quite an icefall, but traveling straight up or down the bowl would require a lot of traversing back and forth to avoid a crevasse fall. And of course there was a massive ice-cliff at the bottom of the hanging glacier. Thankfully we were able to avoid all visible crevasses by traversing high and skirting the rim of the glacier bowl, eventually gaining the mellow ridge between the lower summit and the summit ridge proper. Quinn pulled in rope as I joined him at the start of the summit ridge, a bit confused as to what I was looking at. I asked if this was the route and he said “yes, but it’s time to go down”. The ulu blade of a summit was being consumed by clouds, and increasingly so.

Between us and the ulu blade of a summit ridge, Quinn pointed out the exposed rock moves one would have to make to continue climbing the ridge; I was barely ever a rock climber, but I can judge it was at least a 5.7X ladder with a knife edge approach, with 2000′ and 4000′ feet of exposure to the east and west, respectively. I laughed at the absurdity of the idea of continuing. That amount of exposure was a bit more danger than I was prepared for, Jalen had said it was a few moves at most. The mountain is aptly-named.

I had been mistaken in believing the earlier shale section was the crux, though the ease of the shale climb should have made my mistaken assumption obvious. The knife edge below the rock move looked as though it would be a lot more reasonable in March or April before the snow started to melt, climbing rotten/refrozen sugar snow on loose rock did not look like a good time. It seemed possible one could sacrifice some elevation and avoid the gendarme by traversing below, but this would involve obvious crevasse danger and would be pointless with the summit in a cloud. So we decided to turn around.

From Double Exposure 2nd Ascent, photo credit Jalen Cox

There is SO MUCH fall potential at this spot it’s comical.

This image resolution is full-size; enjoy!

After returning to town, I looked back at old photos from the 2nd ascentists, and recognized one particular rock feature. The 5.7X rock move had SO MUCH MORE SNOW back in March 2022, the rotten snow conditions we experienced were clearly due to the late-season attempt. The majority of the rock problem we were looking at was covered in snow 2 months (and a year) previous.

I’m glad we tried regardless, thankful Quin took the initiative to keep climbing when my willpower was sapped due to ongoing intestinal distress. This ridge is one of the most beautiful, remote, and unique and landscapes I’ve ever traveled. I believe this may have been the first unsuccessful attempt to climb this peak that actually gained the ridge, considering the first and second ascents via the ridge were 51 years apart. It could be years or decades before anyone else travels those slopes. Or maybe someone will head up there next season.

As it was, I was okay not climbing the remaining 300’ of elevation and half mile to the tightrope on top in a cloud, okay with the photos I had taken in my ignorant excitement (though I do wish the weather had been better and I had used my nice camera). I could see Donnaly Dome dimly from afar. Delta Junction’s and Fort Greely’s lights were visible before dawn. I’m fairly certain I saw Denali with pink alpenglow through a gap in the Hayes Range, and it sure seemed like I could see hills as far north as Fairbanks. They seemed to go on forever. I’ve never climbed so far north in the range, it really did feel like being on a precipice as there was simply nothing bigger further north.

This feeling of awe didn’t really hit me until safely back at camp, when I was able to process the climb. So often I’m numb to wonder while climbing; while solely focused on movement and safety, it can be hard to have the mental space to appreciate awe in the moment.

The return trip was pretty uneventful, mainly awful for me due to indigestion. I kept wanting to cut corners, take shortcuts, anything to get me back to the camp latrine faster. Twice I tried relieving the pressure on route, but my bowels would not perform. Something in my last pre-prepared meal did not agree with my system, though the previous few days of consuming the same food had been fine. I’m gonna blame days and days of rehydrated potatoes. My crampon also continued to fall off with increasing frequency, despite my using a small amount of gorilla tape to reinforce the withering cord. It lasted until the final downclimb, where I recall angrily shouting “fine, then I’ll just use one crampon!” when my damaged crampon fell off immediately after equipping it.

Throughout the return downclimb and return trip, the thought of “retirement” from mountaineering seemed so desirable. I recall noticing my aluminum lightweight crampons had already dulled from one use in the mountains. “Don’t care, I probably won’t use them much more anyway”. The question is: are these intrusive thoughts how I actually feel, or are they a coping mechanism to deal with the anxiety? How many distance runners have lied to themselves “just one more mile” because it gives them relief? As I relaxed at the latrine I was finally able to release a few comically-long farts and experience multiple types of internal peace. Food was not appealing that morning, so I unpacked and went to sleep around 10:30AM as the expected storm hit.

We slept, laid, and sat around the tent all day Sunday and Monday, I had enough time to write two trip reports (hello!). A few snowstorms hit our camp from the north on Sunday and we weathered them well 4ish inches of snow accumulated on the glacier, all light fluffy powder. I purposely didn’t wall in the tent entirely so some of the snow could blow downglacier when the winds inevitably picked back up. Sure enough, on Monday there was a southern series of windstorms, probably gusts up to 30 mph. Hard to tell when you’re safely tucked behind snow walls! There were periods of bluebird sky, followed by whiteout conditions. This oscillation continued all day. We contacted Jessie and planned to chat in the morning about a pickup. Before going to bed, I exhumed the snow anchors around the tent while the snow was still soft. They had formed into 20-30 pound blocks of snow with little parachutes connected to the tent that serve as anchors. Crushing a ball of ice is one thing, but sawing out a rock-hard anchor would be more work, so I’m glad I thought of this pre-bed task.

We got up around 6 or 7 and noted there were still some winds, but the sky had finally cleared. 9AM approached the winds died down considerably, and Jessie landed shortly after. I asked him if he’d mind doing a couple loops around the Basin so I could take some photos, he was game. We did one big loop around the valley as we gained altitude, and a second where we flew over the O’Brien Icefall and got a view of White Princess’s north face. I got the photos I wanted as we flew past the Old Snowy/Blackcap ridge, then over the 8,000′ pass we had previously gained on our Double Exposure attempt. As we flew back to Delta Junction and landed, green returned to our color spectrum and overwhelmingly so! Spring had turned into full-blown summer, the brown replaced by magnificent green. As Quinn and I drove down Golden Eagle Road, we spied the monsters of the Hayes Range peeking out over the bright-green fields and I had to stop to take photos.

On our drive north on the Richardson Highway, we stopped a few times to take more photos, noticing for the first time Double Exposure, Blackcap, Little Princess were all visible from the Richardson Highway. Previously this view had appeared as a massive wall of rock, but having flown and climbed on the north side of the Deltas I could now pick out the definition of the ridges.

Driving a little more north, we found excellent views of the north side of both the Deltas and Hayes Range. My allergies flared up before we got back to Fairbanks, I dropped off Quinn and saw a number of friends before sleeping up at Jeff Benowitz’s spare cabin on top of Ballaine Hill. Quinn and I had discussed flying into the Deltas or Hayes if weather was good, but unfortunately a haze had set in over the range, so we grabbed some breakfast at Lulu’s before I took off south towards loved ones in Anchorage and a pure-white Alaskan husky soon-to-be-named “Delta”.

Retirement

I’ve been very lucky in my past 2 seasons in the Deltas, 2019 and 2023; in 2019 I soloed Rum Doodle and Triangle, then with a crew I climbed White Princess via the SW ridge. A three year romance arose from that trip, blossomed, and died before I climbed another peak in the Deltas. In 2023 I climbed to the top of both Item and Institute, the latter solo. This Old Snowy Basin trip has taken me to two peaks I’ve wanted to visit for over a decade.

In contrast to my recent seasons, I spent a number of years (2012-2016?) throwing myself at the Deltas, becoming president of the Alaska Alpine Club before I had climbed a single peak in the Deltas. I climbed Silvertip twice early on, but much more commonly slogged up the Castner one day only to slog down the next day. The various reasons for lack of attaining summits range from inexperience, to laziness, to not taking my endeavors more seriously. Perhaps I was more excited about the idea of climbing than the climbing itself, I’ve had my hopes crushed by a cloud, snowflake, or slab so many times. It gets demoralizing.

Over the last decade, the roller coaster that is climbing anxiety seems to be heightening in it’s drops, but the corresponding excitement peaks themselves aren’t getting any higher. To be properly prepared for mountain season, a climber must have excellent fitness, flexibility in schedule and expectations, and be open to sudden changes in plans. These types of people are getting harder to find in my own generation, as they are all developing strong attachments in town like the good adults they are. When driving from Anchorage, the fewer other people involved in climbing the more success trips tend to be. It’s a hard commitment to drive 5 hours one way for iffy conditions/weather. If you live in Fairbanks, one can usually drive home the same day as one skis out.

This is all to say the more and longer I’ve climbed, the more my preferences have changed. After my experience on Forgiveness, my passion to climb ice was seemingly-permanently quenched. Whether that was due to the avalanche, the glory of a coveted second ascent, or something else, I don’t know. I’ve climbed ice maybe a dozen times since then, but it’s just not that interesting to me anymore. And so too do I observe my climbing interests yet again changing. The more peaks in the Deltas I ascend, the fewer I want to ascend. This is of course how lists work, as you cross items off they are no longer “items”. I made this joke about “Item Peak” after climbing it this spring.

The success I’ve had during my last two springs in the Deltas has done a fair amount to quench my passion for these mountains; instead of being excited for all the cool experiences I could have, my mind fixates on what could go wrong so I’m better-prepared. I watched my beloved dog Kiro slowly die of nose cancer for nearly a year; this experience gave me a lot of compassion for those whom death touches and helped me better understand the value of a single life. People worry about me in town and I have social responsibilities that are interrupted by scheming and climbing the Deltas. Days and weeks of anxiety precede a potential trip, impacting my sleep, memory, and focus…all of it dispelling afterward, leaving me feeling empty and without direction, taking weeks more to get my mind elsewhere. My brain has a tendency to obsess, and while this can help me achieve incredible feats it also strains my ability to switch focus and keep what’s important at top of mind.

This season especially I’ve noticed the domestic cost to mountaineering in the Deltas, mostly in increased anxiety surrounding and during trips. I am a mess of anxiety when I’m climbing, with few exceptions. I’ve had to learn to control it (a useful skill), and I do my best to manage expectations, but still the chatter is often relentless until I am out of the danger zone and headed back to camp or car.

Anxiety-provoked thoughts haunt me before, during, and after the trip: am I going to summit? How will I feel about the trip if we don’t? What if we turn around for the wrong reason and miss a summit opportunity? What will conditions be like up high? How quickly could weather change? Are we going to get winds up high? At which point does my skill distort my perception of safety on difficult-but-climbable snow? Do my warning bells go off anymore, or is that just the usual level of anxiety while climbing? Should I have climbed that? Why did we turn around? Could we have made it?

I don’t know if these thoughts will ever go away, or if they should. I do my best to notice them without feeding them in order to keep a rational calm mind.

The answer to all of them, of course, is “we’ll see”. But my anxiety is not content with that. It gets annoyed and frustrated trying to predict the unknown, and lately with all the various gear required for glacier mountaineering (though maybe that frustration was just indigestion). These g*ddamn pickets that won’t stop jangling about, no matter how I rack them; the rope coil gets stuck on the wands on my backpack and tugs at my torso; a crampon repeatedly falling off, or a boot buckle comes undone every 5 minutes traversing snow…to the point climbing this season was less-often immediately enjoyable. Was it ever? Or was I simply less-anxious about the whole ordeal? I’m certainly climbing at a higher level than I was a decade ago, but more knowledge and skills feed stress. Anxiety clings to life via whatever purchase it may find, much like a climber desperately clinging to a crimp. Climbing these days is mostly a gift to my future self, a temporary sacrifice in mental health for memories, photos, and the experience to reflect upon. These experiences are valuable, but lately I’ve noticed that value feels deflated with accumulated ascents.

It’s hard to write those words, but it is my experience and has lead to much consideration of a “retirement”. At least…retirement from actively pursuing the Deltas in the winter/spring (specifically) to avoid the anxiety and to allow other areas of growth in my life. I’ve barely scratched the surface of summertime in the Deltas, this interests me greatly and may be where I am drawn towards in future years. The compulsion of obsession erodes my mind and I need some sort of freedom from it. To have climbing be a choice, not a need.

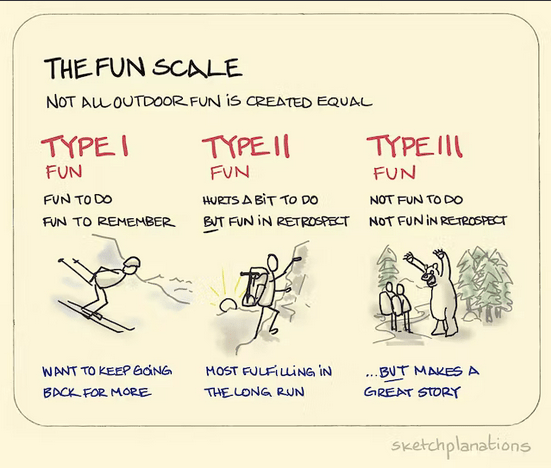

Fear not, fellow climbers, I’m still interested in trip invitations, and if my friends want to go out I’m game. But I don’t want to be the initiator anymore. I would love to climb Silvertip again or ski Item Peak, as the views are amazing, the climbing is easy, and the ski out is truly Type 1 fun. Despite these bright points in my memory, most of my experience of climbing these days is more commonly Type 2/3 fun.

When I was newly learning and exploring the Deltas, there was a sense of wonder that permeated the climbing experience. Although wonder still occurs, it has been blanketed in familiarity. I don’t want to say boredom…but the mind adapts and normalizes even the extreme. In his book, Hitchhiking Up Mount McKinley, Jeff Benowitz quotes a non-climber friend, “so let me get this straight, the essence of alpine climbing is simply about doing harder and harder routes till you die on one of them?” This is not the path I want to take, even though the mountains I climb are nowhere near the same extreme as discussed in the book. There is always danger outside of my control.

In terms of retirement, I still have summer objectives in the Alaska Range that mainly involve exploring ridges in the Deltas, as well as trying to climb a particularly massive peak in the Central Range. I still love climbing, but I have grown to hate anxiety more. I’m feeling like I’ve passed the period of my life that contains the tradition of a yearly spring pursuit of Delta peaks. Right now, retirement feels like a release from this 10+ year project of actively pursuing summits, while still remaining open to possibilities and opportunities, especially if skiing is involved. I know climbing can be actively enjoyable even if anhedonia is infiltrating the experience.

Every time I leave town, I feel like my life has TBD stamped on it until I return. It’s always been that way, I’m just less-able to ignore it at 33 years old than at 23. In the olden days, we used to only tell one person when we were leaving town to climb mountains. That way, fewer people worry and climbers are self-reliant in case of emergency, which strengthens commitment and resolve. At least…that was the theory.

Writing these words while camping on an icefield we flew into, getting nightly weather updates from Rick using an inreach I borrowed, I can laugh at the foolishness of my younger self and his conception of “self-reliance”. Shortly before leaving for this trip, two young climbers died on Moose’s Tooth. Their bodies hadn’t been located, but as soon as I read the conditions under which they went missing I knew they were dead (triggered an avalanche high on a ridge, never retrieved their skis after a few days). I never want to be the focus of an Alaska news story about a missing climber, and the deaths in the Alaskan climbing world have gotten closer and closer to me over the past few years. Ryan Jonson. Evan Millsap. Travis McAlpine. The thought of “getting out of the game” has become more appealing with time, though McAlpine’s non-climbing death shows one is never truly safe.

I started learning to downhill ski because after decades of snowboarding, splitboarding is only properly enthralling when steep. The next level to mountain climbing involves steeper terrain, bigger mountains, and more exposure. That’s certainly one direction I could grow…but I like Type 1 fun more. A lot of good ski runs don’t begin at the top of the mountain, they begin somewhere lower. My philosophy with life is to engineer it to accumulate as many happy and fun experiences while minimizing the probability of unwanted unpleasantness, and that is my goal with “retirement” from my springtime-in-the-Deltas obsession. I want to open mental space for other springtime activities, while still keeping in mind the things I love about mountaineering. I’ve learned to identify when conditions for climbing are probably good and that is the most valuable knowledge I’ve gained about the Deltas.

Half a year later, as I update this post, I can already feel the desire to climb in the Deltas rising as the first snows of the season fall. I’m putting out feelers to fellow climbers, making tentative plans…has anything changed? Hard to say. I know what hasn’t changed is my desire to be free of the obsession. Obsessions are one of my superpowers, they drive me to great accomplishments, but also can bring unnecessary misery to my life through overindulgence and tunnel-vision.

Can one love something without obsessing over it? I believe it is possible to create this dynamic for myself, though challenging.

There’s plenty of activities that gets me in the mountains, like mountain running, crust skiing, ski traverses, and hiking, that make me fulfilled in different ways uniquely their own. These activities involve much less anxiety and danger than chasing rime-covered glaciated summits, and between climbing seasons I’ve experienced how much more there is to a mountain aside from the peak. To be literal, the summit is a relatively tiny portion of any mountain. For now, retirement means I’m going to plan my springtime activities closer to Anchorage and work on growing my attachments in town, focusing more on the terrestrial and less on the ethereal, to see where this path leads. I need this obsession to break, but I don’t want to give up good experiences in the mountains. Maybe a mental break from the Deltas is what I need, rather than a physical break. It’s hard to judge how I’ll feel in 2024 once climbing season arrives again.

With Kiro gone, my life has altered. Without the responsibility of a dog with severe separation anxiety, I have much more freedom of movement to explore Alaska. I wanted to use that freedom to have an awesome Kiro-worthy spring, and that I’ve had. I’ve done something awesome every week since he died and have taken his tag nearly everywhere cool I’ve gone this spring, from the Snowbird Glacier, Explorer Glacier, Tour of Anchorage, the Oosik 50k, Curry Ski Train, Arctic to Indian traverse, Institute Peak, Old Snowy, Double Exposure, and various crust skiing adventures. I specifically didn’t bring it on Item Peak because my gut told me Kiro would not have approved, given the cold. As I move onto the next phase of life with new dog named Delta, I’ll note that “delta” can mean “change over time”, a great metaphor for life.

I suppose over the next decade I’ll see where my interests and obsessions next draw me, what “retirement” will actually mean. In my mind it’s one thing to obsess, plan, and anticipate mountaineering season in the Deltas all winter, and entirely different to go on a whim when good weather arrives or be invited into someone else’s trip, so maybe that’s the difference I need. Maybe I can shorten the amount of time I have to experience anxiety prior to a trip by having no expectations. Part of me still wonders how I’ll feel when conditions are amazing in the Deltas and I have no one to climb with, that will be the true test of this mental shift I’m trying to engineer. I must find a way to break the obsession, which paradoxically might help me enjoy climbing again. Perhaps there are even higher levels of anxiety I’m unknowingly chasing via townlife, but that answer is as unknowable as the weather in the Deltas a week in advance. I suppose we’ll see!

Stumbled onto your page looking at some old photos of the Deltas. So pumped to see your photos of Double Exposure, and some of the other gems of the Deltas. I climbed Double E with Jim Bouchard and Jim Lokken from the Obrien Icefall side (south, near Old Snowy) back in….maybe 78 or 79? Almost got swept away in a big slumping slab, and straddled the summit ridge. What a knife edge it was.

Jim Bouchard and I (and Sputnik the dog) climbed the NW face in maybe 81. It was epic. We skied up the Silvertip branch off the Castner, then down the July Glacier. Some hippie chick saw us from the Thayer hut, and came down and started skiing up to the pass with us. By the time we got there, it was blowing and late, so she ended up snuggling in our cave with the two of us and the dog! That was entertaining.

We went over the pass the next morning, and Jim unroped Sputnik because he was jerking all around, and the dog punched through a bridged crevasse and fell maybe 50 ft. Jim roped up, and I lowered him down to pull him out, but the dog was really spooked for the next few days. We got down to below Double E late that day, and camped.

We got down below the face and in the morning just hiked up a ways to take a better look. Jim had Sputnik chained to a boulder down on the Glacier, and left him his pad to lay on. The face looked so good that we just kept going and pretty soon we were on the lower snow face. It went up through some gullies with verglas and rock, and then opened up onto a big ice face (maybe 700ft) that bulged out in the center to around 75 degrees. Frickin steep anyway. Some sketchy leads later, we made the summit at about dark. We could hear Sputnik howling 4,000′ down on the glacier.

We waited until the moon came up, and started stumbling down the ridge. We tried the west side of the ridge, but it dropped into a hanging glacier that was all mixed up. So, we had to ascend back up the ridge and go further north east. We stumbled into camp about 6 in the morning after 22 hours of climbing. Sputnik had chewed Jim’s pad into about a thousand pieces.

I remember Jim asked me to share my pad with him, and we used rope and packs for insulation the rest of the trip. That was perhaps the finest alpine face route I had ever done. Neither of us had cameras to capture how beautiful it was.

So, it was wonderful to see your pictures, and relive that climb. Jim is in Anchorage, still fit as a fiddle, and I moved to the lower 48, got married and lived life. I grew up climbing in the Deltas, with Forays in the Hayes range, and around Denali. Will always carry those memories with me like a treasure.

Thanks so much for taking me back. Matt VanEnkevort