With a potential 10 year rematch/reunion with Mount Hayes out of the question due to weather, our thoughts turned towards unexplored familiar terrain as Plan B. I drove to Fairbanks from Anchorage after work, slept in Quinn’s driveway, getting maybe 5 hours of rest, before driving us both to Delta Junction. We met up with our pilot, Jessie of Golden Eagle, who loaded our gear into his Cesna 180 and has us in the air by 8:50AM. Before lift-oft, I described the area at which I wanted him to deposit us; he had never landed here before but seemed confident it was possible. We cruised southeast from Delta Junction: large foothills looming before us and even larger mountains loomed behind them. As we flew west of the 4000’ cliffs of Double Exposure, we banked and swooped over the 8000’ elevation col on the southern portion of the ridge as I took photos. Jessie circled around the icefield a few times to drop altitude and gave the snow a love-tap to test snow density. The snow was hard-packed and we felt the plane bounce off the initial pass. Jessie circled around once more as I continued to take photos, and before I knew it we were landing in the Old Snowy Basin.

We landed around 9:10AM, unloaded our gear, and Jessie flew out by 9:20AM. Quinn and I looked around, startled by how strong the crust was. I probed a few preliminary pokes into the snow beneath us, consistent snow was all I found. Jessie has deposited us near the top of the Old Snowy Basin, an icefield on the north side of the Deltas. I’ve never heard of anyone flying in here because usually folks ski in. It’s only 12 miles from the road. But in late May, even during this unusually cold spring, the slog up the Castner would be a horrendous mixture of isothermal snow on top of loose rock, all sitting on a melting moraine. No thanks, I’d rather climb.

Most Delta climbers would consider flying into such a relatively close location cheating, and while I 100% agree, I would argue the isothermal approach negates this argument. This icefield has so much potential for classic climbing, and all peaks are under 5 miles away from camp, as well as no more than 3,000’ above the icefield.

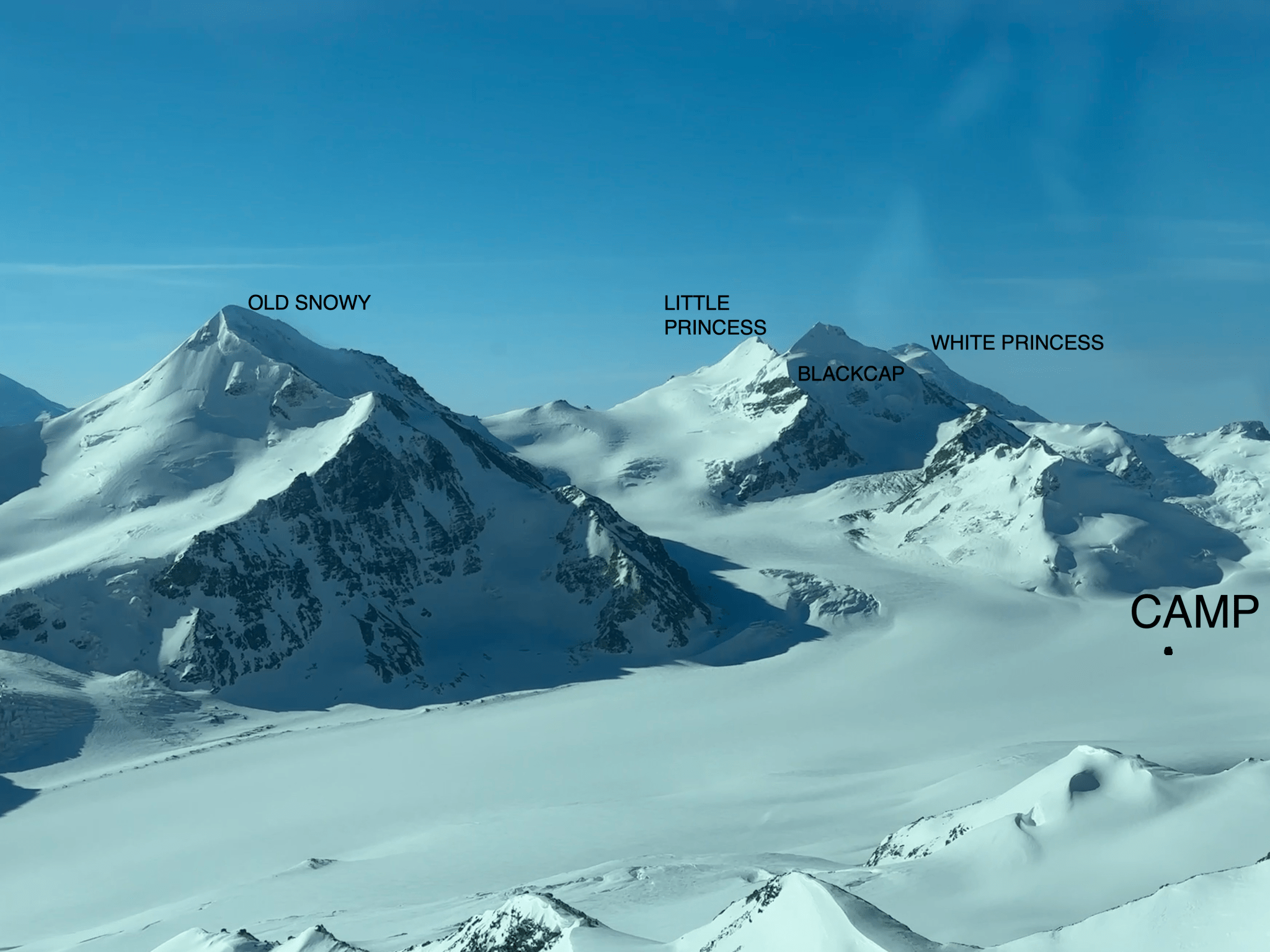

To the south, the icefield climbs a few hundred feet higher before dropping dramatically to the Castner Glacier via the O’Brien icefall—very familiar terrain. To the west, the various 8750′ peaks formed the west wall of the icefield, with various ridges descending to the east. The north-south ridge is capped on the north end by Double Exposure. To the east the glaciers branch and head up to Old Snowy (9700’), Blackcap (9800ish’), and Little Princess (9700’, not visible from camp).

Quinn and I quickly stomped down a tent platform and I insisted we attempt Old Snowy, since the weather and conditions were fantastic. We set up the tent, roped up, and skied east up the Old Snowy Glacier.

We ascended a glacial hill, the left side of which was severely crevassed. The crevasses seemed mostly contained on the northern (left) side of the hill, but as we crested the hill started to notice various large suspicious lines crossing the glacier in a disturbing fashion. Cursing to myself for not following the guidebook I’ve read dozens of times (written by Stan Justice and available at Beaver Sports): the guidebook that specifically recommended avoiding the “domed up area” as it conceals barely-covered crevasses, so we turned right a bit and traversed away from the top of the hill until the buried ice seemed more continuous.

The views of Blackcap were pretty incredible. 9 years previous Galen and I attempted to climb the right skyline of the photo above and got within 300′ of the summit.

The photos below show the dramatic foreshortening that occurs on this mountain. You can…almost see the summit from the base. Watch how the rocks near the summit get both smaller and closer together as we approach the base of the peak. Those rocks didn’t used to be as exposed, see the below photo from 2010 from the old Alaska Alpine Club website:

I always thought it would be cool to climb the west face via those emerging rocks and call the route “Climate Change is Real”, as they’ve slowly melted out more and more over the last decade I’ve observed them. Eventually an actual rock route might emerge.

Once we were a bit further up the valley we turned left and headed for the Old Snowy Ramp. Can’t miss it, the Ramp is the most obvious feature on the mountain aside from the shiny glaciated summit. We gently crossed the invisible bergshrund (people have fallen in), deeply buried by the incredible amount of snow in the Deltas this year.

We left our skis at some rocks at the base of the Ramp and decided not to climb that route; it had been baking in the snow for a few hours (10AM), it was now 12:30PM. We opted for a non-traditional route that follows an obvious gully that bypasses the Ramp and cuts through the rockband. Our route to the south ridge has probably been done before, but the Deltas guidebook doesn’t note it. The travel was slow-going, both due to the exhausting heat and steep terrain. Not steep enough for me to use technical ice tools, but sustained steep.

Old Snowy is no joke. I let myself believe it was no big deal, as climbing the west ridge from camp was just 3 miles one-way with merely 3000’ of elevation gain. Ugh.

This route is more like 2.5 miles up with the same elevation gain. Lots of steep and slow climbing led us out of the gully and onto the west face. I had no inclination to climb the deadly glacial ice of Old Snowy, but Quinn found some near the top of the south ridge he tooled around on. We mostly climbed a path that connected various rocks and skirted between the lower edges of the southern ridge cliffs and summit glacier. It was incredibly exhausting. I had been running on 5 hours of sleep for a few nights in a row and hadn’t been doing much cardio, as my surgical hip needed a lot of rest recovering from a hard ski season. I blamed these factors for my struggle, but most likely the climb was just hard because of the steepness. There are some experiences that do not improve with age, hard labor being one of them. 10 years previously I would have struggled up the face and reveled in the discomfort. These days I don’t tend to seek out discomfort as much as achievable challenges.

After lots and lots of elevation gain, we finally made it to the southern summit ridge, which ended up being longer than expected. We saw no need to rope up here, as the glacier seemed like an icecap rather than a valley glacier. There was just enough snow to provide good footing while still allowing us to note a lack of crevasses…not a single crack or hole in sight. We passed through a few rock bands before walking up to the gently-corniced glacier-capped summit that reminded me of glaciated volcanoes in Iceland.

But in the Deltas, you never know if someone’s climbed a route but just never told nobody

The following are collections of various photos featuring different mountains in the area, taken from the south and west, from different vantage points I’ve visited. I lead each series with the Old Snowy perspective.

White Princess Group

Trip Report Blackcap, Trip Report White Princess

White Princess Group, as seen from the south from Institute Peak

Panorama from Triangle Peak in 2019

Snow White

Silvertip (and Item)

Silvertip Trip Report 1, Silvertip Trip Report 2, Item Trip Report

Double Exposure

Tusac

Hajdukovich

Kimball

As I looked east towards more complicated climbing objectives, such as Tusac (5 miles away), Hajdukovich (7 miles away), as well as the unnamed beauties (8980, 9.5 miles away) my main thoughts were “ugh, f*ck that”. My mind found this thought quite amusing, as this season the thought of retirement from the Deltas has been on my mind and this mental reaction of repulsion is a relatively new one.

Regardless, the landscape was beautiful despite my lack of desire to climb it. The Gerstle Glacier is the main attraction; Old Snowy, Little Princess (2 miles away), White Princess (4 miles away), Snow White (8.5 miles away) make up its western wall. It is incredibly long, ranging from near the northmost to the middle of the Deltas to the at Snow White, then turns sharply east as the Johnson Glacier below Gakona Peak, the centerpiece of the Deltas (13 miles away). Tusac looked a lot more formidable than the last time I saw it a few miles to the south from White Princess. I could even see Mount Kimball, 29 miles away, on the far east side of the Deltas. My camera sounding like a machine gun, I took in as much of the scenery as I could. It’s rare to have a summit day, let alone one with few clouds and mild winds. My fingers even retained their circulation though the photo session!

The downclimb was uneventful but for taking an alternate route down around the base of the summit glacier and descending via the obvious snow ramp. The top layer of snow was prone to sliding when warm, and unlike our route the ramp was a low enough angle we weren’t worried about it avalanching.

The traverse across the western face took a while, our crampons were balling despite anti-ball plates. I was incredibly thirsty and had been eating snow since we started the climb; I found my mountaineering axe regularly balled up with snow, so I used it to obtain dense snow better for eating.

Quinn was ahead of me and immediately headed to the shaded west side of the Old Snowy Ramp. We descended in the shade until it ran out; I glacaded down the rest of the ramp and Quinn followed in a jagged path. When he met me at the skis, it was apparent his sore throat from this morning has blossomed into actual sickness. We skied back to camp, specifically avoiding the domed up area on the north side of the eastern glacier branch. Quinn dropped his pack at camp and immediately crawled into his sleeping bag, dead to the world. I stayed up to start construction on camp, anxiety/excitement too much for my brain to let me rest.

Update: I contacted Stan Justice, he has no record of this route being previously climbed. He asked us for a route name, Quinn and I decided “Sick Dog”, both because of Quinn’s illness and in memory of Kiro.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Fulfillment and Retirement

Quinn and I discussed climbing and it’s relation to our lives. By my estimation, Quinn lives to fly and climb, he pursues both passions relentlessly. I’ve been finding my lust for glacier-mountaineering sated after my triumphant comeback following my four year lapse due to hip injury/surgery. Quinn has found the opposite: as he’s become more skilled as a climber, so too has he found his interest in hard climbing increasing. Both of us lament the ability to find available partners for our pursuits, most of my partners have formed strong attachments closer to town and pursue those as a form of fulfillment. I’ve tried this and it does work for me, but maintaining a social life doesn’t bring the same fulfillment as climbing for me. Nothing does.

There’s a feeling after a particularly hard day of mountain climbing, a sense of peace and tranquility that cannot be disturbed or marred, except by sleep. I noticed that glorious feeling after climbing Old Snowy, and as I woke up the next day noticed it’s disappearance. What a short high.

Sure, my body was still sore and I only slept a few hours, but it was a different day and the sense victory had passed. There is no basking in the ascent the day after, at least not for me. Already my mind was looking towards my next target, eyes shifting from the east to the west wall of the Old Snowy Basin.

This change of attention has been a part of my mind I ever since I was 18 and started hiking on my own before/after work: there’s always another mountain. I once climbed Flattop, Peaks 2 and 3, Flaketop, and Ptarmigan, all peaks on the same ridge, then hiked back over all of them. I know this mindset is not sustainable, but haven’t done much to quell it; how does one quell curiosity when it merges with obsession?

I love getting to a new vantage point and seeing how the landscape differs from my previous perspective. One can only truly understand the shape of the land by viewing it from separate locations. The Deltas are fantastic for this: the terrain is big enough to be discernible from miles away, and each massif is usually between 1-10 miles away from each other, and near 30 at the furthest (Kimball). Each massif contains valleys, ridges, and hanging glaciers that are only visible from certain aspects, all part of the same maze of icy valleys and rimed ridges that I’ve come to love exploring. I had no idea Blackcap had a hanging glacier until I saw it with my own eyes up close. Tucked away on the north aspect, it’s barely visible from the Castner Glacier. I have since seen this hanging glacier from at least 4 nearby peaks, initially on my first (and only successful) Alaska Alpine Club trip: up Silvertip.

I love helping new climbers learn, the skills have always come naturally to me. Simply being in the mountains with other people is enjoyable. I don’t ever recall learning the french technique, I just turned my feet sideways and flat going up steep snow because it was easier. Self-arresting also came easy, even on my back with my head downhill, though like my crevasse skills I’ve never had to use these rescue skills on a climb. I helped out with most activities the Alaska Alpine Club runs through their class during my time in Fairbanks, from knot-tying to crevasse rescue to helping manage the Club. After moving to southcentral Alaska, I continued to volunteer with the Alaska Alpine Club on club trips as I had in college. I understand the difficulties in finding volunteers for spring trip leaders for the Club, having lead the club for a few years, so I did my best to be available for a few years after graduation.

Rick, Grant, and I (all former members/leadership) helped out with the winter camping class portion for a couple Februaries, which was quite enjoyable. We made multiple attempts at Triangle Peak the day after the class, “since we’re already there we might as well”. None got us to the top, but it was fun to be out with friends in the mountains. One year we even convinced some students one year to explore further up the valley, giving them directions on how to access the good part of the moraine (the Lake Ridge, as it’s now known). We had a great skintrack to follow for at least a few miles when we skinned up that afternoon to make camp for Triangle.

Our last winter camping class involved a Deltas sense of humor that seemed to have evaded the class. We wrote messages like “only 1 more mile!” in the snow for the class to discover as they slogged 3ish miles on their way up the Castner valley to the campsite. They didn’t understand yet the seemingly endlessness nature of slogging and perhaps the humor was off-key for newbies. We had a good time that weekend watching the next generation of climbers struggle and learn to clear the lips of, and extricate themselves from, the pretend-crevasses on which we had set ice anchors. It’s always fulfilling to see someone figure out this skill. I ascended using my modern glacier gear rather than prussics, clearing the lip with a jumar was easy.

I haven’t led a camping or climbing trip in years; the drive is just too far and I’ve had to organize and cancel trips from a distance due to weather, which is always a bummer. Most of the trips involved slogging up the Castner only to slog back the next day. Selfishly, I preferred to use the one or two good spring weekend weather windows for my own climbing objectives anyway, and the Club takes care of itself eventually as more people cycle both through the class and into leadership. Teaching new climbers how to mountaineer is fulfilling and had I stayed in Fairbanks I would have remained active in the Club, but I’ve had to move on to committing to a life in Anchorage. Except…I wasn’t quite done with the Deltas. Maybe I never will be.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

While sick Quinn slept, I spent two days building camp, and with this knowledge fresh in mind decided it would be worthwhile to elaborate a bit on

PROPER WIND WALL CONSTRUCTION

I did much winter camping in my Boy Scout years. We never built wind walls and I recall going home from school because kids wouldn’t stop asking me about my swollen windburnt face. I didn’t even notice until they started asking! Mountaineering tents are much stronger than Boy Scout grade tents, and if you have a Stefenson tent you don’t need walls. For everyone else, strong and stable wind walls are essential to weathering storms and wind on glaciers.

Begin by assessing the snow for hard layers to use for snow blocks. I usually start by building a latrine, 1) because they’re important and 2) this allows me to check snow density a few feet down. This trip I constructed a mighty shitter, much superior to the Fortress of Solitude in 2014. I watched the sunset on Blackcap and Old Snowy, noting our trail was visible on the latter from miles away. I got to bed shortly after 1AM, as in addition to being too riled up from climbing, I also wanted to see how much daylight was available at night. I dug out the front vestibule before sleeping.

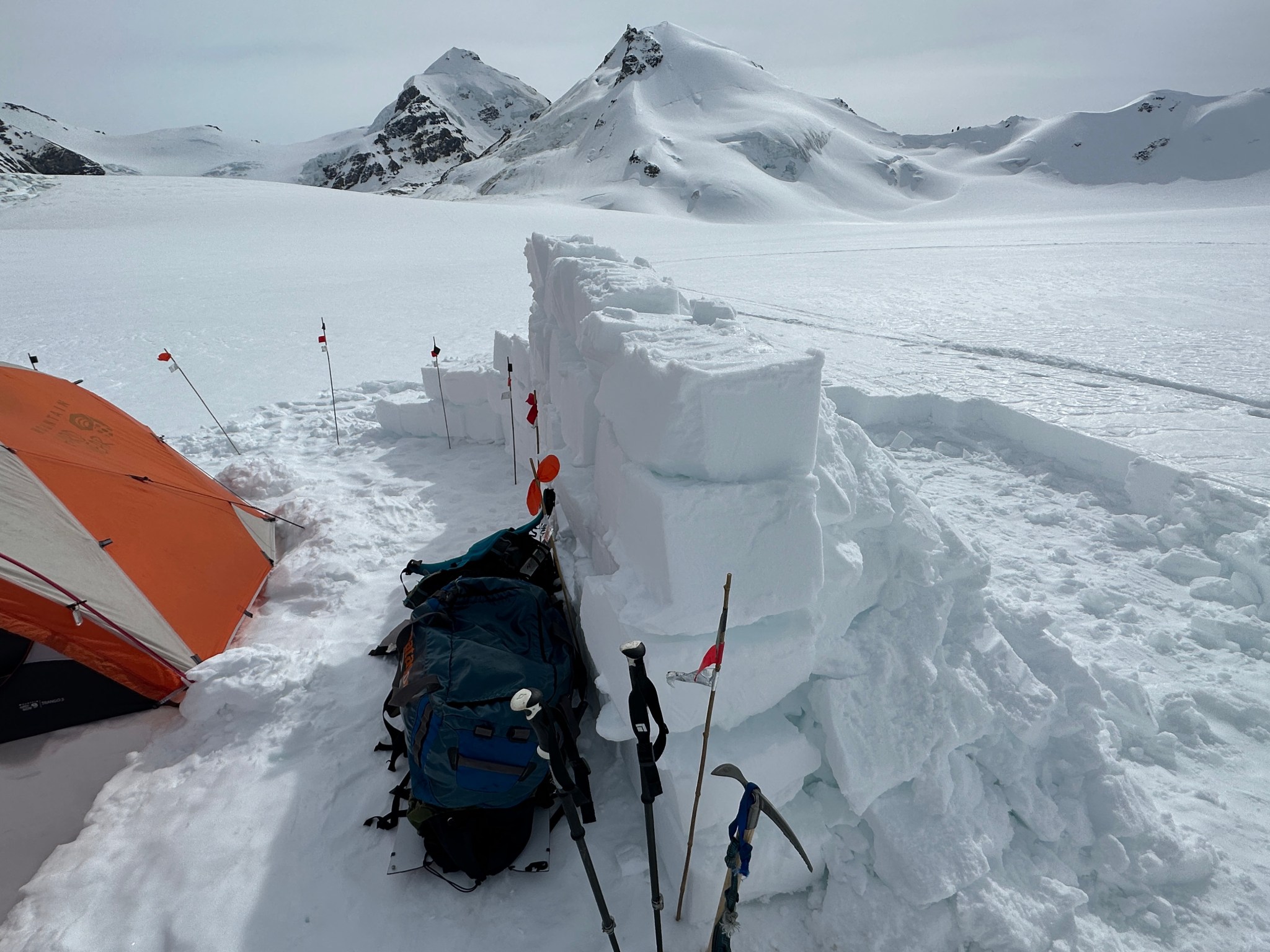

The next day Quinn remained dead to the world. The climb the previous day had clearly done a number on him, though we were both grateful we had climbed. A weather report from Rick let us know to expect high winds from the south around 10AM; I woke up at 10:45AM, heard the tent rustling, and started building wind walls on that aspect shortly after.

There is an art to building camp, exponentially easier and faster with multiple people. I’ve had a solid camp built in about an hour with 5 people for 3 tents. One person cuts snow blocks, a few others extract, carry, and place the blocks, everyone else backfills WITHOUT knocking over the walls. It’s extremely important to backfill your snow walls, which means filling in the windward side with snow all the way to the top block. This allows the wind to flow over your windwall rather than squarely hitting it. It strengthens the wall considerably.

The person cutting blocks should cut the quarry as close as possible to the permanent location of the blocks (I didn’t do a good job of this on the first wall). A good backfill has slightly less than a 1:1 slope, depending on how sticky and compressive the snow is. If your wall is to be 5’ high, your quarry for snow blocks should start at least that far away, and further away in the spring when snow melts/shrinks in the sun. I find using extra snow blocks to initially backfill is an efficient way to add volume quickly, then flip your shovel to hoe-mode and bury it all.

I used wands to mark the future wall’s interior to keep things straight. It’s best not to build your walls too much bigger than your tent, but also you’ll want to be able to walk around the tent to shovel it out and stash gear safely behind the wall. The wall should be approximately the height of your tent to adequately block the brunt of the wind.

Since I was the only person building camp, I had to stage my activities. As it was still sunny, the heat softened any sunkissed snow after an hour. I started building the southern wall and immediately backfilled a fair amount so the wind wouldn’t blow it over. The heat would cause the snow to condense and melt, so while the wall can be very strong once it refreezes it requires a larger amount of snow than in the colder months. I excavated a perimeter from which I could mine snow, and let this snow sit in the sun while I worked elsewhere. An hour later, it made for great soft backfill!

Cutting snow blocks is easy with a snow saw, which I had. Transporting them is a hassle; for a while I slid the larger foundational blocks into place on my shovel. Sometimes I would pick them up, but this quickly dampened my gloves so I tried not avoid this. After the initial blocks are set, it’s time for hole-filling. The blocks shrink in the heat, so any cracks between blocks that can be filled will extend the longevity of the wall. Sometimes you have to cut a custom block of snow to fill weird trapezoid spaces.

Once the first layer of backfill had warmed in the sun, I worked to collapse it by beating it with my shovel. Followed by more backfill. After the backfill is the height of the wall, I start smoothing it out, filling voids, and resmoothing. This also extends the lifespan of the wall by making it more dense and harder for heat to infiltrate through cracks. That’s the meat and potatoes of camp construction.

It’s also quite handy to dig out vestibules for your tent. Not only does it makes getting in an out of the tent much easier and more comfortable, but digging out your back vestibule makes it less likely you’ll set your tent on fire while cooking snow.

The camp I made took 2 days of work for just me, though the second day was mostly adding a 6th layer of blocks and additional backfill. I also saw a solitary high mountain raven, which seemed interested in our camp as it visited Friday afternoon and Saturday morning. Quinn emerged from the tent Saturday afternoon and walked the perimeter of the snow wall. He seemed more lively, no longer on the devil’s doorstep. We chatted about how he felt sickwise, and he felt good enough to climbing this evening. Saturday late afternoon we took a solid nap to get a good few hours of rest before the long night to come: it was time to attempt Double Exposure.

3 thoughts on “Old Snowy”