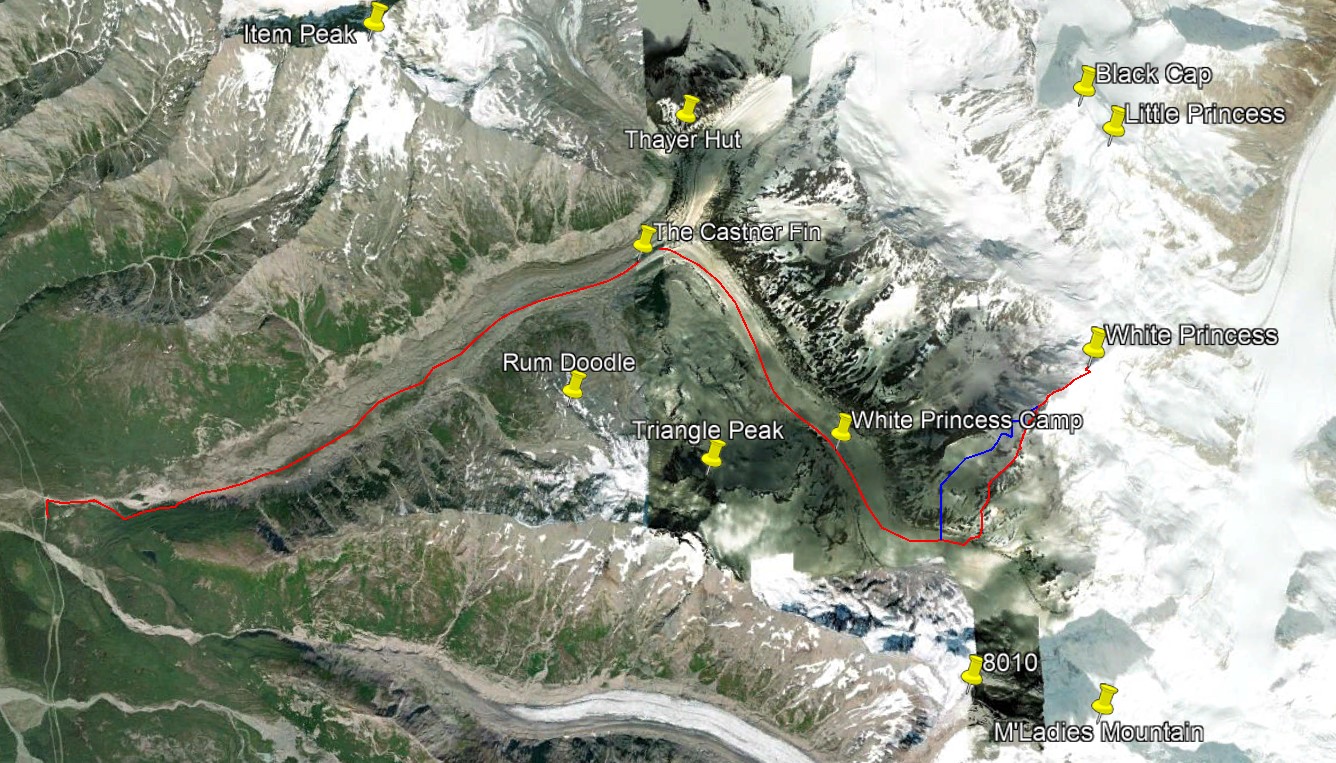

Still basking in the bliss of my March trip to the Deltas, I felt desire to go into the big mountains wane and fade. I entertained myself by crust skiing in Glen Alps before work, and when the crust left Anchorage I truly thought I was done with snow therapy for the year. Less than two weeks after I had last left the Deltas, I was contacted by one of the young climbers for whom I had left a note, a friend named Jalen. He and 4 others were planning to attempt White Princess, a peak I had sought after for years. In fact Jalen and Quinn were both part of this 5 person group, and had been with me on an Alaska Alpine Club trip I had led years previously in 2017, unsuccessfully attempting to climb White Princess via the north face (so unsuccessful we didn’t even make it off the glacier due to waking up late. That wasn’t the first time I’ve done that unsuccessful trip). Since that trip, Quinn has successfully climbed that route.

This time, he and the rest of this crew were interested in the southwest ridge of the mountain. I was familiar with the route, as many of my friends had climbed it years before. I had a feeling I’d be able to get the time off work and indeed my manager acquiesced. This time I only requested half of the following Monday off….I was fairly confident we could do a 3 day trip in 2 days without getting back at 6AM. With my addition, our fellowship now numbered six and we began coordinating gear and plans over facebook messenger. I rarely traveled with a group this large, but everyone had some experience in the mountains…which meant I wouldn’t be taking care of anyone, as can happen on the Alpine Club trips I used to lead. There was a bit of snarkiness shared in the group conversation that I both stoked and appreciated. The prospect of going into the mountains with a fun group dynamic in is quite attractive.

My roommates again agreed to care for my dog and, even with more time to prepare, I still made it out of town late around 6PM Friday. I stopped by Great Harvest to pick up a loaf of bread filled with white chocolate, berries,and cinnamon raisins for breakfast and the slog. The drive to the east was…somewhat eventful. It was the latter half of April, but already I was speeding past RV’s out to enjoy the apparent onset of summer. Just as I found myself feeling joy for having passed a series of RV’s and semi trucks on a stretch of the Glenn Highway, I was stopped by a flagger at the beginning of a construction project. After 15 minutes of waiting for the pilot car, I was moving again but still behind slower vehicles.

No sooner had I past the last semi, I started to see snow-covered vehicles in the opposing lane of traffic. As I passed Caribou Creek, I drove into the tail end of a storm. The falling snowflakes started to increase in size, but thankfully the majority had already fallen. Night fell even as the snow did, and I reached Glenallen around 10PM. Hastily gassing up and grabbing candy for bonus mountain snacks, I drove north. As I passed the Gulkana Glacier, I noticed what appeared to be a small city or a festival, based on all the light.

I wasn’t far off: the yearly Arctic Man was going on, essentially a week-long party for skiers and snowmachiners alike. I took note of the fresh snow on the sides of the road.

I reached the Castner pullout before midnight, and was greeted by the smiling faces of Devin, Quinn, and Camille. Sure seemed like a good crew. I hadn’t seen Quinn in what seemed like (and may have actually been) years.

Doing a quick head count, I came up two short. I inquired as to the whereabouts of Jalen and Zach and was informed they had car issues outside of Fairbanks. They returned to trade out vehicles and left Fairbanks again, only to find they had left critical gear behind and had to *once again* turn around.

“Oh, so they’re not sleeping.” I remarked. Welp, we were planning to wake up at 3AM and I was eager for sleep. I bedded down in my car a bit after midnight and heard Jalen and Zach arrive at some point.

Good. They were my rope/camping team and I didn’t fancy being the fourth person in a 3 man tent or carrying a tent all on my own.

We left the cars around 4:30AM. As we approached the Castner Creek, we noticed there were other cars parked close to the bridge. We made our way up the moraine with a clear and starry sky above us and a few inches of fresh snow laid everywhere. I chose to break trail for the majority of the slog, partially out of selfishness but also out of prudence.

Prudence: I knew my own fitness level and didn’t want the others to waste any energy breaking trail when it would be relatively easy for me. I had a lot of experience venturing up the moraine recently, and knew most of the hills. The trick on the Castner moraine in 2019 (and maybe currently) was to never climb to the top of a hill, always to go around the one of the sides. If a skier chooses the correct path up the hilly southern moraine, it’s possible to have a nearly-constant downhill path skiing down the valley. If the wrong route is chosen, a tired mountaineer will have to expend energy double-poling up the many pointless rolling hills at the end of a long trip.

Selfishness: it’s cool to be that guy breaking trail.

As the sun rose, we became aware of the increasing depth of fresh snow, more than just a couple inches. The clear blue skies foreshadowing afternoon heat encouraged us to keep skiing. Five miles of skiing from the road I spied two figures in the distance. As we approached I recognized one of them as Andrew Cyr, an Alaska Alpine Club member and hardman I knew from my college days in Fairbanks.

Andrew spoke first: “Been a long time since I’ve seen the likes of you ’round these parts. Don’t you live in Anchorage these days?

What, did you guys start skiing at midnight to get here this early?”

After I explained our early start, Andrew and his partner laughed and told us they skied out the previous evening in a light snow and got a foot of powder dumped on them while they camped.

“We decided we were done here. Y’all’ve got a skintrack up to the Confluence, but no further. Have fun!”

I gestured towards the skintrack behind us, letting them know it lead all the way to the highway. We parted ways and continued up the valley.

We reached the Confluence, 7 miles up the valley, before noon and skied directly up the M’Ladies Branch, sticking to the moraine on the southwest side, just north of Triangle Peak. After a little while we roped up and continued skiing uphill in the unrelenting cloudless heat; I recommended not stripping down to base layers in case of a crevasse fall (it is significantly colder in the shade of a crevasse). However, I abandoned that advice about half an hour later, seeking to avoid both heat exhaustion and soaking my clothing in sweat. The sun adds at least 50F degrees.

Around 2PM we climbed to the top of the biggest glacial hill we could find and made camp. We decided it was not worthwhile to haul camp any further up the valley, as the majority of the ridge was now in sight. We probed the hill for crevasses before unroping. I was fairly confident we were on solid moraine and well out of crevasse danger, but wanted to be play safe with this many people. Surly enough, we were camped on solid rocks.

As we set up camp, Quinn and I discussed our options. I was a bit hesitant to head up White Princess with the fresh snow, but Quinn was adamant he thought it the route would go. A good friction to have on a trip, in my opinion, is between caution and ambition. Not knowing much about the route itself, my main concern was traveling from the glacier to the ridge and potential avalanches on the lower slopes. As we finished setting up camp, Quinn decided to wander up the glacier to scope out the base of the route. While he was gone, I ate dinner and dug a snow pit to evaluate the conditions. I noted there was a layer of crust below the fresh snow—the crust was the weak point for the snow structure, any snow on top slid easily. Below the crust, everything was relatively solid. And especially shallow, as we were on top of a moraine.

Quinn returned with news he saw a way onto the ridge from the glacier and had pictures to boot. I informed him of the snow conditions, noting the fresh snow potentially sliding would likely present the highest risk.

We prepared our small packs for the next day to expedite a quick alpine-style departure. Having a small sense of foreboding, I warned everyone the weather tomorrow was not forecasted to be sunny and beautiful as it was today. I’d been learning the best way to avoid disappointment was proper management of expectations.

Don’t set expectations. If you must, set low expectations and be pleasantly surprised.

I’ve had this experience before; the hubris that sets in from approaching a climb on a cloudless day can lead to great disappointment when the party wakes up the next day inside of a cloud, a complete whiteout. That happened the first time I sought after White Princess, the first (but not the last) time I never even got off the glacier during an “attempt”. I’ve learned to never assume weather will be stable, just accept it as it is at the time and make do.

We woke up at 2AM the following morning. Even though I had a good feeling, the sensations of anticipation or excitement rose with me from my sleeping bag. The back of our tent was oriented towards White Princess: I unzipped the back door of our tent and was greeted by a moonlit peak and a sky full of stars. Not a cloud in sight.

I guess we’re climbing today.

This provided ample motivation for me to rise from slumber, but not enough for my tentmates. I’ve played this game of chicken before. It took them about 15 more minutes to motivate themselves out of their bags, only after which I unzipped, exposed myself to the cold, and began preparing for the day.

Everyone needed some water, but most of that work had been done the previous evening. Jetboils would provide water for us en route, so Quinn and I both packed ours. I put my boots on my already sore feet, realizing today was going to be a day filled with foot pain.

As we gathered outside, my headcount landed at five, not six. Someone explained Camille had felt ill and decided to stay in bed. Don’t read meaning into it, there are no such things as omens. Especially in the big mountains, I find my mind tries to divine the future from little things. This is a mental artifact from my religious upbringing I’ve attempted to scour from my belief system. A sick partner isn’t a sign of a doomed trip or a sign of foreboding. Things just are, no more or less.

Our party headed out along Quinn’s skintrack, some with red headlamps and others with white; I opted to forgo any illumination as the moon was quite bright.

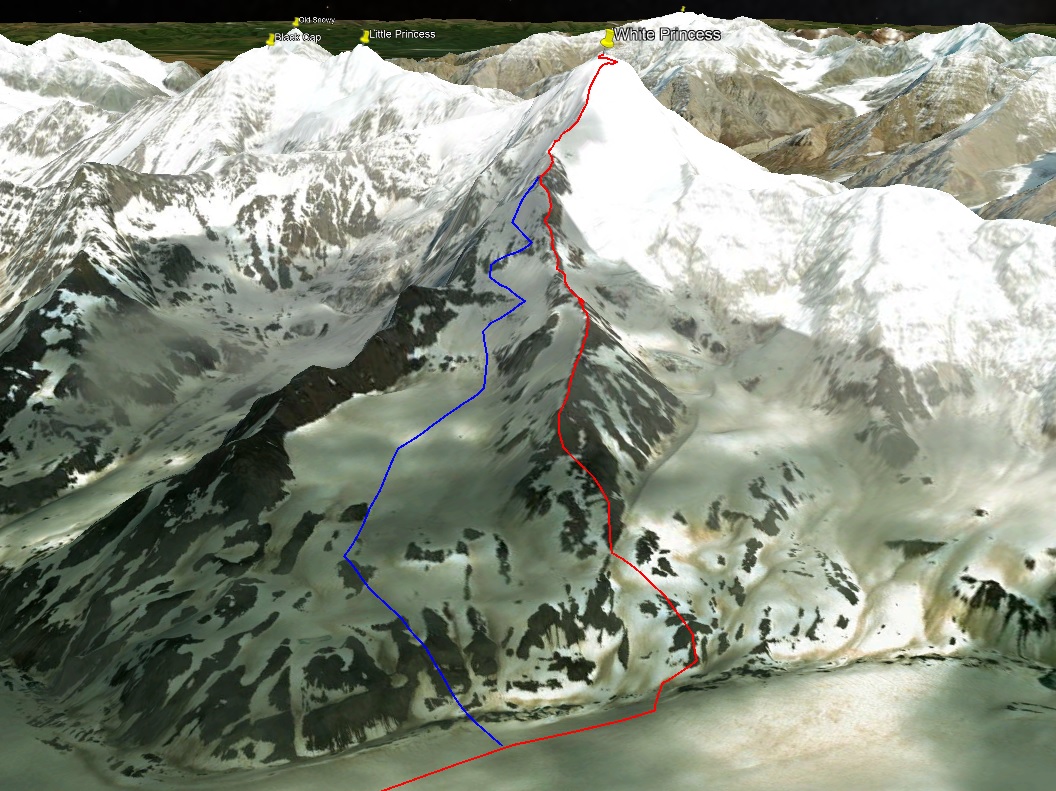

As we reached the end of Quinn’s skintrack we passed briefly into a mountainous shadow. Things were so dark I could hardly make out the ridge we were to climb. We gathered together and Quinn showed me a photo of White Princess’s SW ridge he took the previous day. Slowly, we pieced together the ridge’s outline from barely-discernible features and followed it to the glacial floor of the valley. Gotcha. We roped up and made our way towards the base of the ridge even as the moonlight faded and dawn bathed all.

As we skied off the glacier and onto the mountain, the temperature seemed extraordinarily cold. We’re at 6,000’ elevation, I reminded myself and remembered how hot it was just 12 hours ago. The peaks of the Hayes Range, lit with the beginnings of alpenglow, were just peeping over the tops the local mountains. Rather, we just beginning to peek at them.

We skied across a small valley and towards the rocky ridge. When finally on the mountain itself, we unroped and took a food break. I set off to take care of morning human business and the light glacial wind licked my bare ass, numbing it quickly. Scarfing down a handful of chocolate coffee beans, I rejoined the group and we began to ski up the lower slopes leading to the southwest ridge.

We skinned and skinned until the slope became too steep and required crampons. Appreciating how long the process used to take prior to years of experience, my crampons were on my feet and splitboard on my back before inactivity could chill my body. The others followed behind. Moving up the left side of the ridge, I took joy in scrambling over rocks and boulders as I once did in childhood. Balancing on the points of my crampons and using my poles for stability, I navigated my way up a number of piles of rock before the ridge transitioned to the deep snow I was expecting to blanket the entire mountain.

So much for those negative expectations. Instead of a continuous covering of fresh snow, we found snow with varied thicknesses and densities, and conditions would routinely transition from hip-deep blower powder to solid supportive snow, due to the imprecise effects of the wind deposition. No avalanche red flags whatsoever (I’d taken an avalanche class back in 2015). All through the morning the skies remained clear, though looming in the back of my mind and over the horizon were forecasted afternoon storm clouds. One of the many reasons we got an alpine start.

White Princess’s SW ridge is an extraordinarily scenic and classy route, I only had such a feelings of glory on Pioneer’s North Face and Silvertip. M’Ladies Peak has a ring of glaciers hanging off of it’s face that are balanced precariously and have been perched there for thousands of years. The glacier ringing the mountain seems like it used to connect with the rest of the M’Ladies Branch upon which we made our camp, back when the glacier was much thicker. At the rate glaciers are melting, it will be gone by the time I’m old. The delicate but brutal glaciation of the mountain to the west of M’Ladies, peak 8010, is a feature of the mountain that has drawn my eye repeatedly over the years, it looks like a tiered pyramid.

As we climbed the left side of the ridge, occasionally there would be a break in the rocks that would allow us to catch a glimpse of the southwest glacier that pours off the summit of White Princess, filling the small valley to the right of our ridge. Heavily-crevassed and broken up, it is a wonder to behold and was quite extraordinary to climb beside. Tucked far on the southwest side of the mountain, few people ever see it with their own eyes; it was a first for everyone present. I munched on some chocolate coffee beans as I took in the view.

The first and only major obstacle we encountered was a cliffband on the ridge; as the rest of the group took a break, I scouted upward, found the route cliffed out, and attempted to find my way around the cliffs by downclimbing a ways left of the ridge. No such route was discovered, the snow was hard and the fall potential was great. Doubt entered my mind as it began to focus on time wasted, but I tried not to let these thoughts take too much control. They’re not helpful and foster negative thought patterns. To circumnavigate these cliffs on the left side, we would have to sacrifice a lot of our hard-gained elevation. On the bright side, it was now sunny.

Rejoining the group, someone suggested going around the right side to preserve our elevation. Quinn and Devin poked their heads over the side and did some reconnaissance, eventually yelling back the route would go. Zach, Jalen and I followed their tracks.

From that point, the rest of the ridge is a blur in my memory. I recall keeping in mind the necessity to continue making headway higher without venturing far onto the slope, as a eventually it became clear we were heading towards a distinct point where the southwest ridge we were climbing intersected with the actual west ridge.

We took a break near a corniced part of our ridge, below the intersection point and I cautioned the more inexperienced skiers to leave their skis here, as the upper slopes would only steepen. Devin, Quinn, and I continued to haul our boards/skis up as Jalen and Zach dropped and secured their own. I marked a descent point with a wand. The slope steepened further as we approached the top where the ridges joined, and the final section was loose snow over scree.

We finally reached the point at which the two western ridges met around 8,600′. Dropping our splitboards and skis and standing on a summit of sorts, the next phase of our quest was to walk upon the edge of a knife.

We put on puffy jackets as we ate and took in view of the thin ridge connecting the high point on which we stood to the summit glacier of White Princess, finally visible in all its glory. The ridge was the crux of the mountain and the only really-super-dangerous part. On the right side, the fall potential was about 400′ down to the southwest glacier. The left side fall potential is over 2,500′, depending on how much a falling body bounces and gains momentum.

The summit takes the shape of a 1,200′ stepped pyramid, which rolls down towards the north, west, and southwest, and drops off steeply to the south. Only the southwest portion of the summit glacier was visible to us, we had climbed adjacent to it on the southwest ridge. The thin ridge connecting the point on which we stood to the summit glacier is White Princess’s distinct and unique feature, “the knife edge”, with thousands of elevation drop to the north and rocky cliffs terminating above a broken-up glacier to the south. We discussed who would lead it and I volunteered.

As no gear-based protection from a fall was possible on the knife edge, Jalen and I reviewed the basics of a “Fairbanks Belay”. If I fall to the left, he jumps off to the right, and the ridge takes the weight of the fall. While not ideal, the Fairbanks Belay is preferable to death.

Jalen and I roped together. He belayed me as I stepped onto the knife’s edge. Bolstering my confidence by humming and singing “Highway to the Danger Zone”, the travel was significantly easier than I expected and looked far more intimidating than it was in actuality.

WARNING: This ridge is extremely scenic.

Almost disappointing. The deep fresh snow on the ridge provided a welcome amount of security in footing, at times plunging up to my hips, but it was mostly knee-deep and the messy choss/scree that formed the ridge was frozen and easily walkable.

I belayed the rest of the team in after crossing over. Once everyone had crossed, we remained spread out and worked our way up the steepening slopes close to, but not on, the corniced north edge of the summit glacier. Snow conditions were mostly snice (snow-ice) with a small coat of fresh snow on top, but this tended to diminish as we gained altitude. The fresh snow we found was once again a blessing; where there was harder snicey snow we would often find a line of fresh snow, on top of which we could travel with secured footing.

After the first major steep section, I requested everyone group up so I could collect their pickets; everyone had brought one so we could have five. Pickets are long pieces of metal and are notoriously annoying to carry around one’s neck. Bitching about how much I hate carrying pickets, I clipped all five to a sling around my neck and continued upwards, jangling metal with every step like some broken wind-chime. As the snow was in prime conditions for placing them, I used all but one on the ascent (a bonus of placing pickets was I no longer had to carry them). The rime ice covering the summit glacier was pleasant to travel upon, mainly because we didn’t break through it. Rime ice forms directly from the moisture in the air, generally found in high-mountain terrain. It can transition from bullet-proof to paper thin while never changing appearance and often obscures summit crevasses.

As we climbed the pyramid we also approached our turnaround time of 1PM. I became frustrated with the multiple false summits that we surmounted, but finally the obvious summit fin came into view and all frustration fell away. As I prepared to climb the south side of the summit, and felt my mind try to create an prediction.

We’re going to summit. After chasing this peak for 5 seasons I am finally here. What could possibly stop us?

“A crevasse fall” a wiser part of my mind retorted and all thoughts quieted. It’s nice when problems solve themselves.

There is something incredible about the moment right below a summit, where all thoughts of the future and past disappear and what’s left is fatigue, determination, and a curious awareness of one’s position in the world and the bizarre reality of climbing mountains. It’s amazing how quiet air can be at 9,800′ when everything terrestrial is below you. Isn’t this is the whole purpose of climbing, this moment? We go up mountains to turn right around; what am I about to gain that makes all this effort and energy seem worthwhile? I walked up to the summit fin, which is exactly as described. One last steep section.

As I climbed upwards, I stabbed the shaft of my my ice axe deep into the rime ice of the summit fin. A few feet from the top, I allowed a moment of hubris to overtake me as I turned towards Jalen and casually remarked, “I love this part.” Pulling on the head of my axe and kicking my crampons points into the rime, I hoisted myself onto the summit, walked down the fin and belayed the other two up. Quinn and Devin joined us on the little summit.

Wasting no time, I immediately began photographing the landscape. Four years previously, before my first “attempt” at White Princess I bought a camera with 42x optical zoom specifically to take photos from this summit. After my camera’s battery froze, I used my phone to continue to document the area. I can still picture the 360 view in my mind, it was one of the most spectacular vantage points on which I’ve ever stood. There’s a reason White Princess is the crown jewel of the Deltas, it’s the highest peak in the Range and is visible from nearly every high peak nearby.

A few miles east was Tusac, a formidable peak with dueling glaciers on the west aspect, the top of which visible above Gulkana Glacier when viewed from the Richardson Highway. Very infrequently climbed, Tusac was first climbed by a team from Tokyo and the AAC. Ten miles to the southeast across multiple ridges, Mount Gakona stood tall, rarely observed and almost never climbed. It is the tallest peak in the entire Delta Range and has a spectacular glacier coming down its south side. Further east I could barely make out the monstrous Mount Kimball, a giant battleship of a mountain with a massive rocky hull.

From White Princess itself, my eyes followed the north ridge as it dropped elevation and split to the north and west; it dropped dramatically in elevation to the west as it paralleled the M’Ladies Branch, appearing below as a massive glaciated shoulder, and eventually rose again to become O’Brien. The ridge that split to the north of this shoulder dropped and gained elevation as it became Little Princess and here the ridge again split: to the north to rise as Old Snowy and to the west as Blackcap.

The Hayes Range was distantly in the east and now cloaked in storm clouds. Silvertip stood out to the northwest at a comparable elevation to our own; Triangle and Rum Doodle in the southwest seemed mere infants, as did Minya, Institute, McCallum, and Rainbow directly to the south. The southern ridge of the M’ladies Branch terminated to the east as M’Ladies Peak below us to the southeast, and that ridge split to the northeast and southeast. To the northeast it became an unnamed 8,000′ peak which connected to Snow White; to the northeast it became Sight Peak. That ridge angled northwest and connected directly to White Princess, with impressive glaciation I’d never seen on the northeast side dropping down to the Johnson Glacier. The southwest side of the ridge cradled White Princess’s southwest glacier, along which we had climbed parallel.

Impressive glaciation on the NE side of the ridge from Sight Peak

After about half an hour on top, our awareness was brought back to the present moment and to the existence and speed at which a storm on the north side of the Delta Range seemed to be approaching us. I guessed we had a few hours before it overwhelmed our position, but did not want to make any hard estimates. At this point expectations aren’t useful. We made it to the top and we’re going down regardless. We once again roped up and began the descent.

As much as I hated to leave the heavenly plateau from which beautiful glacial features ruled the landscape, it was time. I led off the summit fin and began plunge-stepping down our old trail as gently as I could. Eventually, feeling elated, I ignored advice given to me by ascentists-past and aggressively plunge-stepped a new path next to our old footprints. No more than five steps later, my right foot met a disturbing lack of resistance as it plunged straight into what I assume was a small but deep crevasse. Catching my weight as my hips met the snow, I lifted myself out with my arms and stared down into the inky blackness of the glacial crack. Hoar frost had collected on the inside of the crevasse, where moisture attempted and failed to escape the icy coffinous summit pyramid. The blinding sunlit snow created an unnerving contrast between the surface world and the mostly-hidden depths of the crevasses below that threatened to consume unwary and arrogant travelers. I informed my partners of my discovery and placed my feet gingerly and respectfully into my old footsteps until we reached the knife edge, which we carefully crossed. The storm had yet to reach us, and I initially gave an estimate we had until 4PM before it might hit. However, feeling cocky from the wave of good luck we had been riding, I cheerfully updated this estimate to “4:30 or something”. No one cared as we gathered ourselves at the 8,600′ intersection of the western ridges.

Forming up at the head of the southwest and western ridges, Quinn, Devin, and I prepared to tee-off on splitboards and skis, while Jalen and Zach downclimbed to their own equipment. Quinn dropped onto the face on splitboard first and found variable windy conditions that improved into softer snow towards the west ridge. Devin followed and skied precariously-close to the corniced edge of the west ridge. I yelled a warning he could not hear, before he made a turn to the south and followed Quinn. I followed the path scraped by both, immediately feeling the lactic acid and muscle fatigue from the previous 36 hours’ efforts. I took no shame in gracelessly shaving the slope back and forth without carving, gaining enough momentum to continue moving but not too much that might cause me to tumble. As the wind-hammered effects on the snow relented and tended towards deposition, I couldn’t resist carving a few S-turns and nearly caught my edge as the snow hardened again.

Towards the middle of the face we turned hard to the north to avoid a rock band, and the snow immediately became soft and powdery, and we all found separate sinuous paths through incredible spring powder to the large valley bowl below. While we rested there, we spied Zach and Jalen walking their way down the ridge and yelled after them to SKI DOWN, FOR THE LOVE OF GOD IT’S THE BEST POWDER EVER!

After a while, we lost sight of them and assumed they didn’t get the message, so we continued towards camp as two separate parties, an arrangement we had discussed before splitting up. Quinn, Devin, and I briefly considered roping up to descend the M’Ladies Branch before deciding against it. We all attempted to ski up the bergshrud/lateral moraine, but could not gain enough momentum to surmount it. Instead we trailed the outside edge of the glacier where snow had avalanched or deposited and found a path onto the glacier when elevation was lower. We intersected our old trail and double-poled back to camp. On my way back, I saw a fourth and fifth set of ski tracks descending the face, indicating Zach and Jalen had indeed received our message!

Each of us five arrived separately and were greeted by a much more enthusiastic version of Camille than the one we left in the morning. With a few more hours of sleep, she overcame the majority of the symptoms of illness she had been experiencing. She spent the day sunbasking and relaxing, and at one point followed our track up the glacier to observe our progress. Until we informed her, she was unaware there were, at this point, multiple storms around the mountains. Camille had thoughtfully melted water for us; I selfishly turned her down, wanting to make my own water and thereby burn some white gas reserves to lighten the weight I’d have to ski out. I overcame this impulse later and graciously accepted from her what water remained. We all looked to the sky; with the valley rimmed by 6000’-9000’ peaks there was still no storm clouds in sight. We spoke theoretically of a protective field surrounding our expedition.

Zach and Jalen skied into camp within an hour of our arrival, and we all ate dinner as we packed and debated the permeability of tent fabric with regard to various particulates. I decided to let my pain-filled feet experience temporary relief from the confines of my climbing boots while I packed, the pain had become nearly unbearable anyway. Quinn, Devin, and Camille announced they were going to spend another night in the mountains to have the opportunity to shred more powder; Zach, Jalen and I had obligations to school and work. As the sun left our campsite, so too did the three of us depart. I wanted to leave Camille and the others with a cool and memorable quote upon departing, but I think I stuck with my classic “until the next time,” before I double-poled away, my long and light skate ski poles finally in-hand.

It’s a strange thing we mountaineers do, leaving the mountains in the evening. Skiing into the sunset away from friendly faces, good weather, and warm powder seems crazy. The knowledge that diligence, experience, and a packed skintrack are the best navigators for 11 miles of slogging towards the road barely helps quell this perception of madness, and might actually enhance it. Unhelpful that the pain in my feet had been in increasing since the previous night and was nearing 7/10 territory on my current pain intensity scale. Vicodin at least took the edge off and my skate ski poles made the process easier, but the slow shuffle after a long day (or two) is always an ethereal experience. In the moment it is generally about two hours full of pain and suffering, but moving toward the goal of an actual bed with real food adds dissonance to the bittersweet experience. Especially in remembrance my mind craves that strange zombie-like state of consciousness, body wrecked from a day of solid climbing efforts, focused only on an object of desire, and the joy of easy downhill skiing at the end of very long day . The deathmarch back to the highway is gone before it can be appreciated, my memory barely functioning throughout.

I love that the top of the mountain can be seen throughout the majority of the valley

I woke up in the back of my Subaru on Monday morning at a pullout an hour north of Glen Allen. I had drove as far as I could the previous night to shorten the drive home at least a little. Shoving my sleeping bag to the side, I continued my slog back to town, stopping only for human needs and coffee…which when put to writing sounds redundant. I arrived in Anchorage before noon and stopped by my apartment to shower and do laundry. Reunited with my dog Kiro, we drove to work and I walked into the office around lunchtime. A raccoon-tanned face and an undying smile were the only indication to my coworkers of my weekend, lest they take note of my new background wallpaper complete with the view from 9,800’.

Afterword: A few weeks later, Quinn and Camille flew out to the Deltas and circled White Princess. Our footprints were still visible!

8 thoughts on “White Princess”