Photo Credit: Galen Vansant

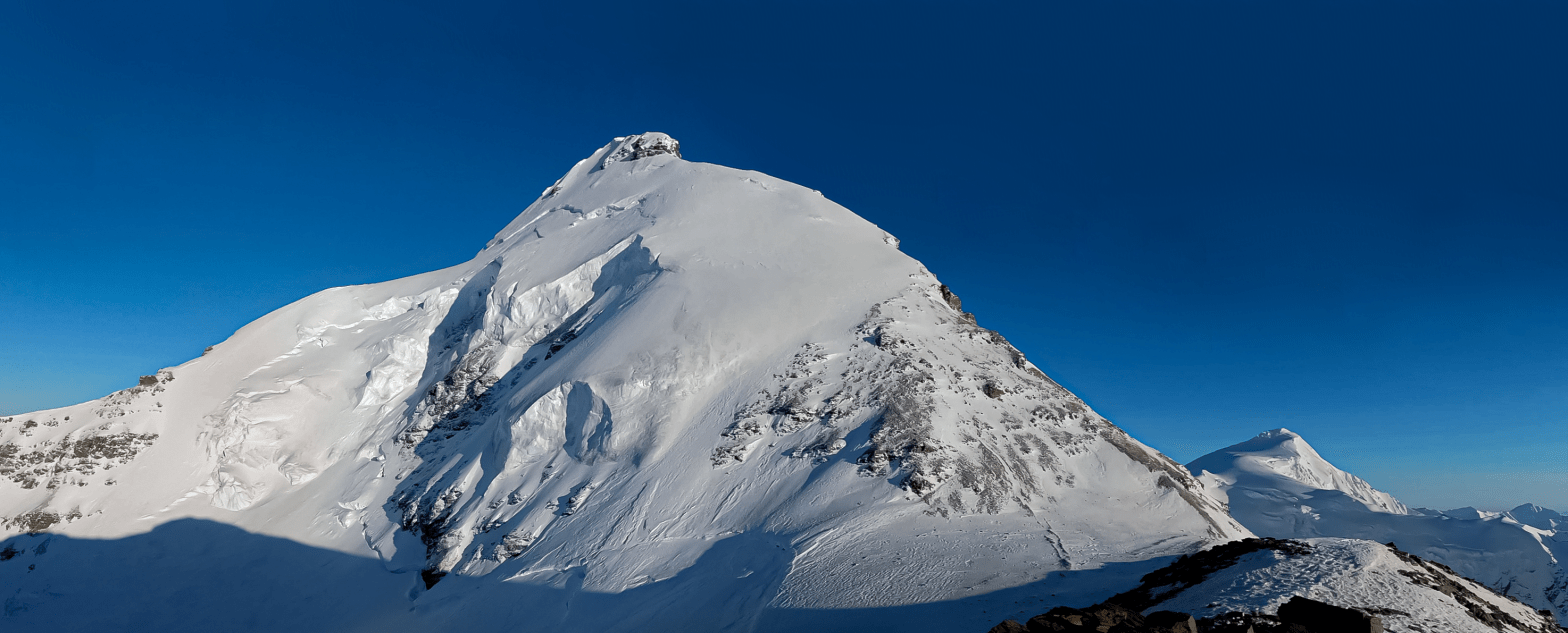

Little Princess (left), Blackcap (right)

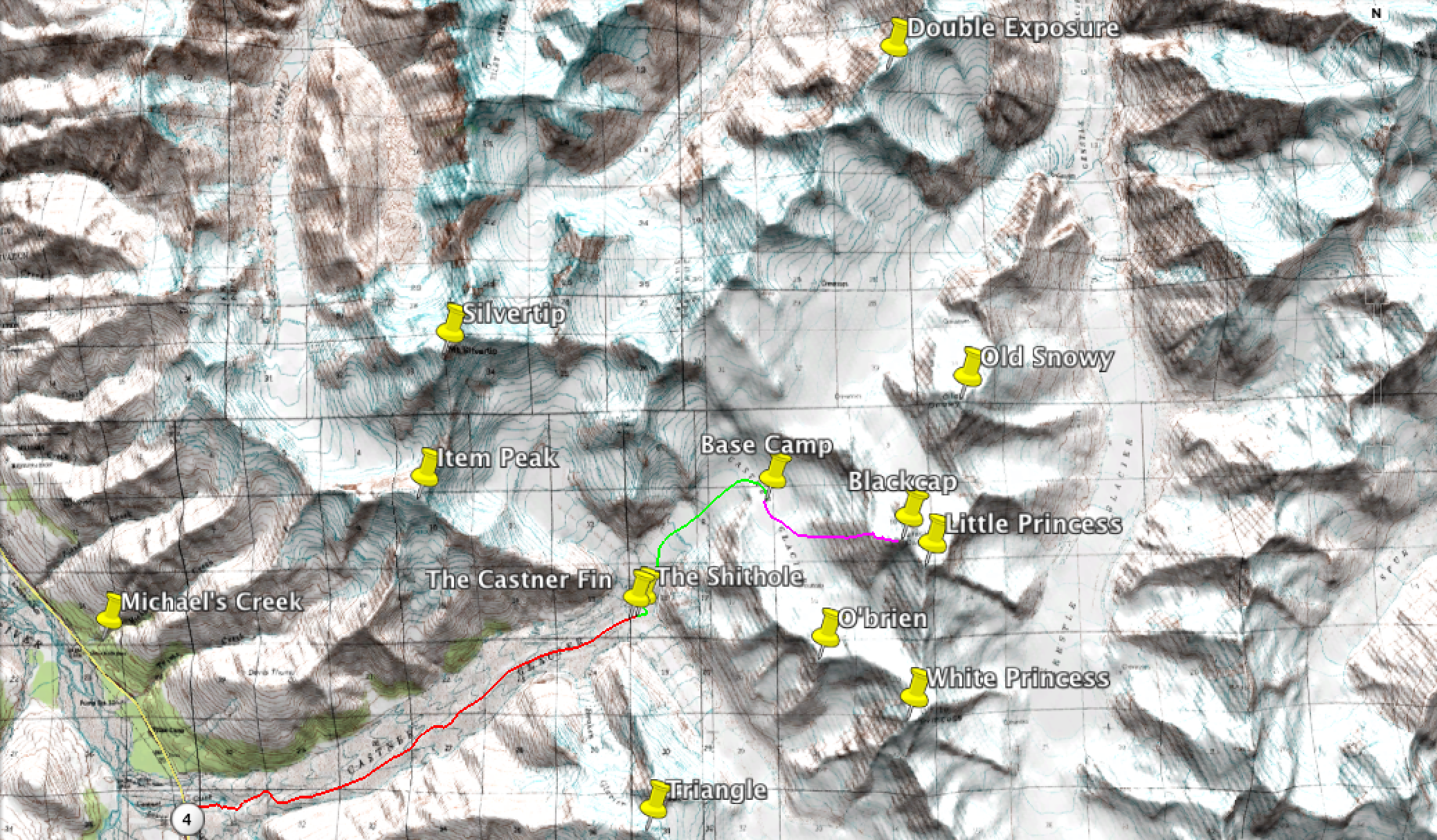

Spring Break was upon us UAF folk. Galen had been playing the role of homeless climbing bum for a few months down in the warmer part of the US, but at the mention of potentially good weather and definitely existing snow, he drove day and night (or at least a night) from California to make it to Alaska for my week off. We had little news about snow stability, but weather was improving towards the weekend so we decided to go with the old standard: The Castner Glacier.

The Castner Glacier is in a notorious part of the eastern-most subrange of the Alaska Range, a subrange affectionately known as “The Deltas”. The Castner is a much-degraded glacier that was much higher in the 60’s and 70’s (300′ higher in places), before dramatically bowing to the whims of climate change. The Thayer Hut is located about 7.5 miles from the road above the Confluence of the Silvertip (left), White Princess (center), and M’Ladies (right) Branches of the Castner. Each of these branches leads to a host of climbing “opportunities”, like Old Snowy, Double Exposure, White Princess, Blackcap…or as I call them, “projects” because I never seem to complete them. Yet the inexplicable draw of this valley calls me back year after year, only to ravage my carefully constructed plans time and time again. I had hoped this trip might break the continuous stream of unaccomplishments I had experienced in this valley. As I write this two years later in 2015, I still hold that hope for a future trip. (***Update from the future: the key to finishing projects is time and perseverance. Someday, I’m coming for you: M’Ladies, Snow White, Minya, and Double Exposure.***).

Weather didn’t start off very good. The approach was very windy.

The second outing of my hauling sled, upgraded with a single attachment point instead of one on each hip. Much more comfortable on the hip muscles. This upgrade earned it the designation “MRK II”. I had been skiing with a pack almost every day for a few months, I offered to take the sled most of the trip.

The trip up the moraine was long; I always forget how much time it takes to slog up (I know it’s around 7 miles). Luckily for us, the crux of the slog, the Fin, was mostly covered in snow so we were able to cruise right over it instead of traversing the slopes around it.

After about 6 hours of slogging up the valley I had a desperate and terrible idea. Our gear collection was still in its poverty phase and we only had my 3 season tent for shelter. I felt it might get battered by the wind if we just set it up. Instead of taking time to build snow walls, we would utilize our resources, so we took a few hours and built a snow cave. People, including myself, have these romantic ideas about sleeping in snow caves. Usually they hold these views until they sleep in one. Properly constructed, a snow cave can be a warm and safe place, out of the wind and insulated by feet of snow in each direction. Improperly constructed, they are a frozen hole good for shivering most of the night away.

In retrospect, building a snow cave into a windward formation was not a good idea. A few snow walls would have taken less time to build and we would have stayed drier.

There also would have been more room in the tent. As we finished our ramen and mashed potatoes and a couple tablespoons of butter, we prepared for a night in our newly constructed paradise. This paradisal image quickly blew away as the evening winds picked up and snow started flirting into the cave. We attempted to plug the entrance with the sled and our packs; while it stifled the invasion to an extent, we did wake up with about a centimeter or two of snow on our already-starting-to-be-soggy sleeping bags.

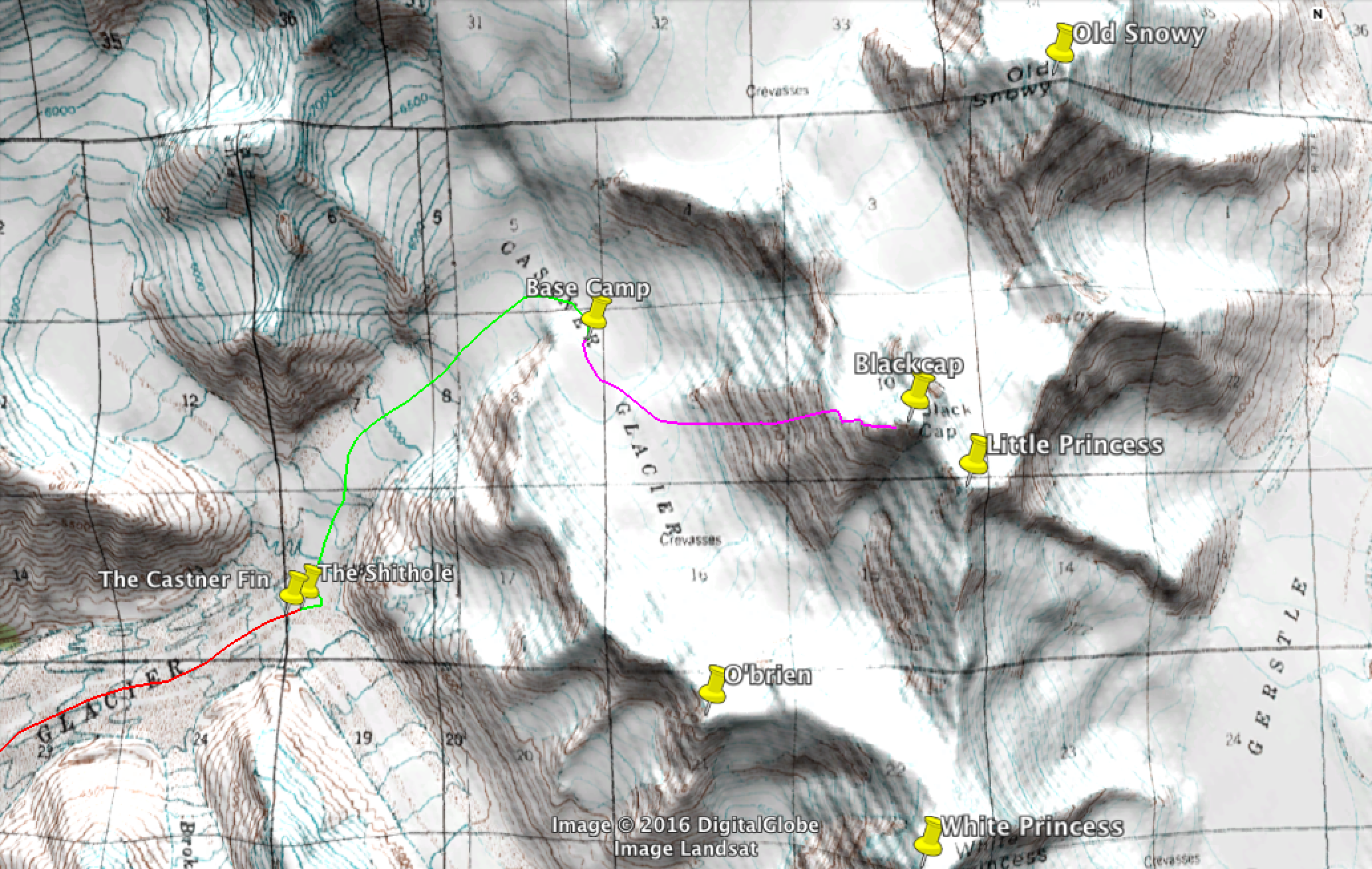

Begin day two. We got out of the newly christened “Shithole” and started the process of boiling water. The first pot took an annoyingly long time, about 45 minutes for a liter. It was quite cold and we came to the realization there needed to be some sort of barrier between the stove and the snow. Probably why they included those pieces of foil to go under and around the stove. And also why shovels have detachable heads, I assume. With the sun returned and the skies cleared, we regained some motivation. We continued up valley and got off the moraine and onto the glacier proper, roping up at the Confluence. We skied up the White Princess Branch through a crevasse field; I had hiked up the valley the previous summer and knew “generally” where to go in order to avoid most of the crevasses.

The best way I’ve found up this part of the glacier is to start far right of the only rock visible at the Confluence, and head left towards a series of chutes up-glacier from the hut plateau (plateau near the base of the ridge separating the Silvertip Branch on the left from the White Princess Branch in the center). From here stay left of center as you travel around the corner, linking exposed rock to exposed rock.

As we ascended the glacier we experienced a fair and uncomfortable amount of “whoomphing”. This is the technical term for, as well as the sound snow makes, when a weak layer collapses somewhere in the snowpack often occurring when a weak layer is overlaid by a hard wind slab (which was present). We (still) had no formal avalanche training because we were young, dumb, busy and poor, but had done a bit of reading about the topic in preparation and whoomphing is definitely one of them red flags, meaning avalanche danger would be high if we were on a slope steep enough to slide. Especially bad was that 360 degrees whoomph we set off near the crest of a glacial roll that circled around us before quieting.

On the bright side, a hard slab on top of the snowpack meant glacial travel was likely pretty safe because most crevasses would be obvious, or covered in a hard layer of supportive snow. We abandoned any idea of trying to push over the O’Brien icefall and instead would look for a route up a peak that involved as little snow travel as possible. We rounded the corner of the White Princess Branch and were overjoyed to see multiple frozen scree lines up Blackcap. We had an objective!

We arrived at our base camp site around 6pm, having woken up around 8:30. To make up for the miserable snow cave, we constructed a mighty snow fortress with three snow walls almost as high as we were tall and reinforced the hell out of them. It was not very windy when we arrived, but winds tend to pick up and roll down the glacier in the evenings.

We constructed a badass latrine, dubbed “The Fortress of Solitude”. This acted as an unofficial 4th snow wall.

The third day started with gorgeous weather and apparently little wind. As soon as we stepped out of the confines of our snow walls, the wind was apparent and biting. The night before we had joked about taking a very inefficient and glaciated route up Blackcap via a cirque on the west side, and in the morning I watched a piece of a hanging glacier (serac) fall and trigger an avalanche right across our theoretical route.

The route up Blackcap started once off the Castner Glacier. We skied until we were across the moraine/bergshrund (the edge of a glacier) and stashed our skis at the base of what we called “the Ramp”, where is the rocky slope climbs 2,000′ from the glacier to the north rim of the valley. We followed scree lines upwards as much as possible up the Ramp from 6,500′ to 8,500′ and turn east to traverse across the ridge until we reached “the Shoulder”, where Blackcap intersects the north ridge of the White Princess Branch of the Castner Glacier. From there we turned north to climb the final ridge towards the summit block (the “black cap”), under which we planned to traverse to access a gully that cuts through the rock to reach the true summit around 9,800′.

Photo Credit: Galen Vansant

Photo Credit: Galen Vansent

White Princess (right), Little Princess (center), Blackcap (right)

Photo Credit: Galen Vansant.

As we reached the base of the summit block, we recalled the guidebook noted we should not follow the ridge up any higher; instead we should traverse to the right, under the black cap, and ascend the gully. We did not experience any red flags on the mountain so far, so we figured we would attempt to traverse onto the more exposed part of the mountain to access the gully. Galen pulled a real dick move here, asking if I wanted to pass the lead off to him “since, you know, I’m single and you’re not.” Asshole! I became very conscious of our altitude (9,000′) and exposure (3,000′) respectively. Traversing off the ridge of the mountain exposed us to the large and steep drop to the Castner.

Cursing Galen, I passed the lead to him and he slowly worked his way out across the slope below the summit block. After a few minutes we both slowed to a stop because as we worked our way across the slope, the snow conditions had changed. We kinda figured this might happen; the snow we had encountered en route so far had been fairly thin, but as we worked our way to the more southern aspect, the snowpack got thicker and the foundation turned from cohesive to loose garbage. We dug a small hole with no resemblance to a proper avy pit and, after finding uncohesive snow was the only thing supporting a hard crust, our minds were quickly decided: neither of us wanted to chance a 3,000′ ride down the mountain merely to gain the summit. The previous year we triggered an avalanche below us that shot down a 1,000′ gully on Item Peak and we learned a lesson there: we turned around.

Photo Credit: Peter Illig

So, still alive, we turned around and went down the mountain. Since we had plenty, we spent some time taking photos on the great shoulder of Blackcap.

We decided to follow the edge of the Ramp down the mountain, which had a little more snow but, not enough we judged, to be a slide danger. Picking our way through the rocks to plunge-step in the snow, we bathed in alpenglow for most of the descent.

We grabbed our skis and returned on our trail to camp. Galen and I split a stick of butter and mixed it in with our ramen/mashed potatoes. Galen proclaimed half a stick of butter is the best flavor of Ramen and I cannot disagree with his assessment.

As a sidenote, a few weeks later our camp was still visible but overblown with snow. Another climbing party spotted it on their way to the Silvertip Icefield, thought it might be a moulin or crevasse, and strove to avoid it. Durability is the mark of a solid camp!

We had a fairly cold start to the morning, but when the sun hit camp it warmed considerably. We left base camp around 12:15pm and got to the car around 6:45pm. The sled was a challenging opponent to tow down the glacier; we opted not to rope up because of the snow stiffness and because downhill skiing gets complicated when roped together. I went first. As I picked up speed, the sled threatened to pendulum to my left and tried to cut in front of me. I jabbed it with my pole and sent it the other way, which kept it at bay until momentum eventually saw it penduluming to my right, so I pushed it back. This game continued the entire way down to the Confluence, where the snow angle lessened and the MRK II calmed down.

The snow had changed significantly over the past few days; the sun had scorched the snow and turned it into wonderful snice, which made exiting the valley a relatively quick process. We also found old tracks that had melted out.

We returned to my cabin fairly baked from all the sun, wind, and climbing and gorged ourselves on bread and beer cheese.

.

7 thoughts on “Blackcap”